- Home

- Mark Twain

Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1 Page 12

Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1 Read online

Page 12

This incredible puppy actually described Gerhardt’s design to the sexton and advised him to make a new design for competition—which he did; and he used Gerhardt’s design in it! The Governor had no more sense than to tell Gerhardt that he had done this thing. Taking the whole thing round it has been the most comical competition for a statue the country has ever seen. It was so ludicrous and so paltry—in every way contemptible—that I tried to get Gerhardt to retire from the competition and make a group for me to be called the Statue Committee to present portraits of these cattle and mousers over a clay image. I said I would write a history of the Nathan Hale committee to go with the statue and I believed he could put it in terra cotta and make some money out of it. But he did not wish to degrade his art in gratifying his personal spite and he declined to do it.

It is customary everywhere else, I believe, for such a committee to specify what is the latest date for the offering of designs and also a date when a judgment on them shall be rendered, but this committee made no limit—at least in writing. Their policy evidently was to give Mrs. Colt’s sexton time enough to get up a satisfactory image—no matter how long that might take—and then give him the contract.

Waller failed to be reelected Governor, but was appointed Consul-General to London and sailed on the 10th of May with the Nathan Hale statue still undecided, although, as he had a personal favor to ask of a friend of Gerhardt’s, just before sailing he said “Grant me the favor and I will pledge my word that the Nathan Hale business shall be settled before I sail.”

Gerhardt kept his clay image wet and waiting three or four months and then he let it crumble to pieces because the prospects of the design seemed to be as far away as ever.

About General Grant’s Memoirs

1885. (Spring.)

I want to set down somewhat of a history of General Grant’s memoirs.

By way of preface I will make a remark or two indirectly connected therewith.

During the Garfield campaign General Grant threw the whole weight of his influence and endeavor toward the triumph of the Republican Party. He made a progress through many of the states, chiefly the doubtful ones, and this progress was a daily and nightly ovation as long as it lasted. He was received everywhere by prodigious multitudes of enthusiastic people and to strain the facts a little one might almost tell what part of the country the General was in for the moment by the red reflections on the sky caused by the torch processions and fireworks.

He was to visit Hartford from Boston and I was one of the committee sent to Boston to bring him down here. I was also appointed to introduce him to the Hartford people when the population and the soldiers should pass in review before him. On our way from Boston in the palace car I fell to talking with Grant’s eldest son, Colonel Fred Grant, whom I knew very well, and it gradually came out that the General, so far from being a rich man, as was commonly supposed, had not even income enough to enable him to live as respectably as a third-rate physician.

Colonel Grant told me that the General left the White House at the end of his second term a poor man, and I think he said he was in debt but I am not positively sure. (Said he was in debt $45,000, at the end of one of his terms.) Friends had given the General a couple of dwelling houses but he was not able to keep them or live in either of them. This was all so shameful and such a reproach to Congress that I proposed to take the General’s straitened circumstances as my text in introducing him to the people of Hartford.

I knew that if this nation, which was rising up daily to do its chief citizen unparalleled honor, had it in its power by its vote to decide the matter, that it would turn his poverty into immeasurable wealth, in an instant. Therefore, the reproach lay not with the people but with their political representatives in Congress and my speech could be no insult to the people.

I clove to my plan, and, in introducing the General, I referred to the dignities and emoluments lavished upon the Duke of Wellington by England and contrasted with that conduct our far finer and higher method toward the savior of our country: to wit—the simple carrying him in our hearts without burdening him with anything to live on.

In his reply, the General, of course, said that this country had more than sufficiently rewarded him and that he was well satisfied.

He could not have said anything else, necessarily.

A few months later I could not have made such a speech, for by that time certain wealthy citizens had privately made up a purse of a quarter of a million dollars for the General, and had invested it in such a way that he could not be deprived of it either by his own want of wisdom or the rascality of other people.

Later still, the firm of Grant and Ward, brokers and stock-dealers, was established at number 2, Wall street, New York City.

This firm consisted of General Grant’s sons and a brisk young man by the name of Ferdinand Ward. The General was also in some way a partner, but did not take any active part in the business of the house.

In a little time the business had grown to such proportions that it was apparently not only profitable but it was prodigiously so.

The truth was, however, that Ward was robbing all the Grants and everybody else that he could get his hands on and the firm was not making a penny.

The General was unsuspicious, and supposed that he was making a vast deal of money, whereas indeed he was simply losing such as he had, for Ward was getting it.

About the 5th of May, I think it was, 1884, the crash came and the several Grant families found themselves absolutely penniless.

Ward had even captured the interest due on the quarter of a million dollars of the Grant fund, which interest had fallen due only a day or two before the failure.

General Grant told me that that month, for the first time in his life, he had paid his domestic bills with checks. They came back upon his hands dishonored. He told me that Ward had spared no one connected with the Grant name however remote—that he had taken all that the General could scrape together and $45,000 that the General had borrowed on his wife’s dwelling house in New York; that he had taken $65,000—the sum for which Mrs. Grant had sold, recently, one of the houses which had been presented to the General; that he had taken $7,000, which some poverty-stricken nieces of his in the West had recently received by bequest, and which was all the money they had in the world—that, in a word, Ward had utterly stripped everybody connected with the Grant family.

It was necessary that something be immediately done toward getting bread.

The bill to restore to General Grant the title and emoluments of a full General in the army, on the retired list, had been lagging for a long time in Congress—in the characteristic, contemptible and stingy congressional fashion. No relief was to be looked for from that source, mainly because Congress chose to avenge on General Grant the veto of the Fitz-John Porter Bill by President Arthur.

The editors of the Century Magazine some months before conceived the excellent idea of getting the surviving heroes of the late Civil War, on both sides, to write out their personal reminiscences of the war and publish them now in the magazine. But the happy project had come to grief, for the reason that some of these heroes were quite willing to write out these things only under one condition that they insisted on as essential. They refused to write a line unless the leading actor of the war should also write.* All persuasions and arguments failed on General Grant. He would not write; so, the scheme fell through.

Now, however, the complexion of things had changed and General Grant was without bread. [Not figurative, but actual.]

The Century people went to him once more and now he assented eagerly. A great series of war articles was immediately advertised by the Century publishers.

I knew nothing of all this, although I had been a number of times to the General’s house to pass half an hour talking and smoking a cigar.

However, I was reading one night in Chickering Hall early in November, 1884, and as my wife and I were leaving the building we stumbled over Mr. Gilder, the editor of the Ce

ntury, and went home with him to a late supper at his house. We were there an hour or two and in the course of the conversation Gilder said that General Grant had written three war articles for the Century and was going to write a fourth. I pricked up my ears. Gilder went on to describe how eagerly General Grant had entertained the proposition to write when it had last been put to him and how poor he evidently was and how eager to make some trifle of bread and butter money and how the handing him a check for $500 for the first article had manifestly gladdened his heart and lifted from it a mighty burden.

The thing which astounded me was, that, admirable man as Gilder certainly is, and with a heart which is in the right place, it had never seemed to occur to him that to offer General Grant $500 for a magazine article was not only the monumental insult of the nineteenth century, but of all centuries. He ought to have known that if he had given General Grant a check for $10,000 the sum would still have been trivial; that if he had paid him $20,000 for a single article the sum would still have been inadequate; that if he had paid him $30,000 for a single magazine war article it still could not be called paid for; that if he had given him $40,000 for a single magazine article he would still be in General Grant’s debt. Gilder went on to say that it had been impossible, months before, to get General Grant to write a single line, but that now that he had once got started it was going to be as impossible to stop him again; that, in fact, General Grant had set out deliberately to write his memoirs in full and to publish them in book form.

I went straight to General Grant’s house next morning and told him what I had heard. He said it was all true.

I said I had foreseen a fortune in such a book when I had tried in 1881 to get him to write it; that the fortune was just as sure to fall now. I asked him who was to publish the book, and he said doubtless the Century Company.

I asked him if the contract had been drawn and signed?

He said it had been drawn in the rough but not signed yet.

I said I had had a long and painful experience in book making and publishing and that if there would be no impropriety in his showing me the rough contract I believed I might be useful to him.

He said there was no objection whatever to my seeing the contract, since it had proceeded no further than a mere consideration of its details without promises given or received on either side. He added that he supposed that the Century offer was fair and right and that he had been expecting to accept it and conclude the bargain or contract.

He read the rough draft aloud and I didn’t know whether to cry or laugh.

Whenever a publisher in the trade thinks enough of the chances of an unknown author’s book to print it and put it on the market, he is willing to risk paying the man 10 per cent royalty and that is what he does pay him. He can well venture that much of a royalty but he cannot well venture any more. If that book shall sell 3,000 or 4,000 copies there is no loss on any ordinary book, and both parties have made something; but whenever the sale shall reach 10,000 copies the publisher is getting the lion’s share of the profits and would continue to get the lion’s share as long thereafter as the book should continue to sell.

When such a book is sure to sell 35,000 copies an author ought to get 15 per cent: that is to say, one-half of the net profit. When a book is sure to sell 80,000 or more, he ought to get 20 per cent royalty: that is, two-thirds of the total profits.

Now, here was a book that was morally bound to sell several hundred thousand copies in the first year of its publication and yet the Century people had had the hardihood to offer General Grant the very same 10 per cent royalty which they would have offered to any unknown Comanche Indian whose book they had reason to believe might sell 3,000 or 4,000 or 5,000 copies.

If I had not been acquainted with the Century people I should have said that this was a deliberate attempt to take advantage of a man’s ignorance and trusting nature, to rob him; but I do know the Century people and therefore I know that they had no such base intentions as these but were simply making their offer out of their boundless resources of ignorance and stupidity. They were anxious to do book publishing as well as magazine publishing, and had tried one book already, but owing to their inexperience had made a failure of it. So, I suppose they were anxious, and had made an offer which in the General’s instance commended itself as reasonable and safe, showing that they were lamentably ignorant and that they utterly failed to rise to the size of the occasion. This was sufficiently shown in the remark of the head of that firm to me a few months later: a remark which I shall refer to and quote in its proper place.

I told General Grant that the Century offer was simply absurd and should not be considered for an instant.

I forgot to mention that the rough draft made two propositions—one at 10 per cent royalty and the other the offer of half the profits on the book after subtracting every sort of expense connected with it, including OFFICE RENT, CLERK HIRE, ADVERTISING and EVERY-THING ELSE, a most complicated arrangement and one which no business-like author would accept in preference to a 10 per cent royalty. They manifestly regarded 10 per cent and half profits as the same thing—which shows that these innocent geese expected the book to sell only 12,000 or 15,000 copies.

I told the General that I could tell him exactly what he ought to receive: that, if he accepted a royalty, it ought to be 20 per cent on the retail price of the book, or if he preferred the partnership policy then he ought to have 70 per cent of the profits on each volume over and above the mere cost of making that volume. I said that if he would place these terms before the Century people they would accept them; but, if they were afraid to accept them, he would simply need to offer them to any great publishing house in the country and not one would decline them. If any should decline them let me have the book. I was publishing my own book, under the business name of Charles L. Webster & Co., I being the company, (and Webster being my business man, on a salary, with a one-tenth interest,) and I had what I believed to be much the best-equipped subscription establishment in the country.

I wanted the General’s book and I wanted it very much, but I had very little expectation of getting it. I supposed that he would lay these new propositions before the Century people, that they would accept immediately, and that there the matter would end, for the General evidently felt under great obligations to the Century people for saving him from the grip of poverty by paying him $1,500 for three magazine articles which were well worth $100,000; and he seemed wholly unable to free himself from this sense of obligation, whereas to my mind he ought rather to have considered the Century people under very high obligations to him, not only for making them a present of $100,000, but for procuring for them a great and desirable series of war articles from the other heroes of the war which they could never have got their hands on if he had declined to write. (According to Gilder.)

I now went away on a long western tour on the platform, but Webster continued to call at the General’s house and watch the progress of events.

Colonel Fred Grant was strongly opposed to letting the Century people have the book and was at the same time as strongly in favor of my having it.

The General’s first magazine article had immediately added 50,000 names to their list of subscribers and thereby established the fact that the Century people would still have been the gainers if they had paid General Grant $50,000 for the articles—for the reason that they could expect to keep the most of these subscribers for several years and consequently get a profit out of them in the end of $100,000 at least.

Besides this increased circulation, the number of the Century’s advertising pages at once doubled—a huge addition to the magazine’s cash income in itself. (An addition of $25,000 a month as I estimate it from what I have paid them for one-fifth of a page for six months [$1,800].)

The Century people had eventually added to the original check of $1,500 a check for $1,000 after perceiving that they were going to make a fortune out of the first of the three articles.

This seemed a fine lib

erality to General Grant, who is the most simple-hearted of all men; but to me it seemed merely another exhibition of incomparable nonsense, as the added check ought to have been for $30,000 instead of $1,000. Colonel Fred Grant looked upon the matter just as I did, and had determined to keep the book out of the Century people’s hands if possible. This action merely confirmed and hardened him in his purpose.

While I was in the West, propositions from publishers came to General Grant daily, and these propositions had a common form—to wit: “Only tell us what your best offer is and we stand ready to make a better one.”

The Century people were willing to accept the terms which I had proposed to the General but they offered nothing better. The American Publishing Company of Hartford offered the General 70 per cent of the profits but would make it more if required.

These things began to have their effect. The General began to perceive from these various views that he had narrowly escaped making a very bad bargain for his book and now he began to incline toward me for the reason, no doubt, that I had been the accidental cause of stopping that bad bargain.

He called in George W. Childs of Philadelphia and laid the whole matter before him and asked his advice. Mr. Childs said to me afterwards that it was plain to be seen that the General, on the score of friendship, was so distinctly inclined toward me that the advice which would please him best would be the advice to turn the book over to me.

He advised the General to send competent people to examine into my capacity to properly publish the book and into the capacity of the other competitors for the book. (This was done at my own suggestion—Fred Grant was present.) And if they found that my house was as well equipped in all ways as the others, that he give the book to me.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 1.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 1. The Prince and the Pauper

The Prince and the Pauper The American Claimant

The American Claimant Eve's Diary, Complete

Eve's Diary, Complete Extracts from Adam's Diary, translated from the original ms.

Extracts from Adam's Diary, translated from the original ms. A Tramp Abroad

A Tramp Abroad The Best Short Works of Mark Twain

The Best Short Works of Mark Twain Humorous Hits and How to Hold an Audience

Humorous Hits and How to Hold an Audience The Speculative Fiction of Mark Twain

The Speculative Fiction of Mark Twain The Facts Concerning the Recent Carnival of Crime in Connecticut

The Facts Concerning the Recent Carnival of Crime in Connecticut Alonzo Fitz, and Other Stories

Alonzo Fitz, and Other Stories The $30,000 Bequest, and Other Stories

The $30,000 Bequest, and Other Stories Pudd'nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins

Pudd'nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the Undead

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the Undead Sketches New and Old

Sketches New and Old The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg

The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg A Tramp Abroad — Volume 06

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 06 A Tramp Abroad — Volume 02

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 02 The Prince and the Pauper, Part 1.

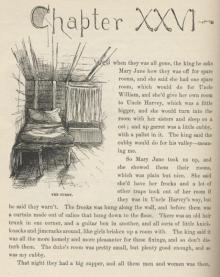

The Prince and the Pauper, Part 1. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 16 to 20

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 16 to 20 The Prince and the Pauper, Part 9.

The Prince and the Pauper, Part 9. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 21 to 25

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 21 to 25 Tom Sawyer, Detective

Tom Sawyer, Detective A Tramp Abroad (Penguin ed.)

A Tramp Abroad (Penguin ed.) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 36 to the Last

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 36 to the Last The Mysterious Stranger, and Other Stories

The Mysterious Stranger, and Other Stories A Tramp Abroad — Volume 03

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 03 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 3.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 3. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 06 to 10

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 06 to 10_preview.jpg) The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade)

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 31 to 35

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 31 to 35 The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg, and Other Stories

The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg, and Other Stories A Tramp Abroad — Volume 07

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 07 Editorial Wild Oats

Editorial Wild Oats Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 26 to 30

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 26 to 30 1601: Conversation as it was by the Social Fireside in the Time of the Tudors

1601: Conversation as it was by the Social Fireside in the Time of the Tudors A Tramp Abroad — Volume 05

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 05 Sketches New and Old, Part 1.

Sketches New and Old, Part 1. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 2.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 2. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 8.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 8. A Tramp Abroad — Volume 01

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 01 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 5.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 5. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 01 to 05

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 01 to 05 A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 1.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 1. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 4.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 4. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 2.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 2. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 7.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 7. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 3.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 3. Sketches New and Old, Part 4.

Sketches New and Old, Part 4. Sketches New and Old, Part 3.

Sketches New and Old, Part 3. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 7.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 7. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 5.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 5. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 6.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 6. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 4.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 4. Sketches New and Old, Part 2.

Sketches New and Old, Part 2. Sketches New and Old, Part 6.

Sketches New and Old, Part 6. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 11 to 15

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 11 to 15 Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc

Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc Sketches New and Old, Part 5.

Sketches New and Old, Part 5. Eve's Diary, Part 3

Eve's Diary, Part 3 Sketches New and Old, Part 7.

Sketches New and Old, Part 7. Mark Twain on Religion: What Is Man, the War Prayer, Thou Shalt Not Kill, the Fly, Letters From the Earth

Mark Twain on Religion: What Is Man, the War Prayer, Thou Shalt Not Kill, the Fly, Letters From the Earth Tales, Speeches, Essays, and Sketches

Tales, Speeches, Essays, and Sketches A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 9.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 9. Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands (version 1)

Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands (version 1) 1601

1601 Letters from the Earth

Letters from the Earth Curious Republic Of Gondour, And Other Curious Whimsical Sketches

Curious Republic Of Gondour, And Other Curious Whimsical Sketches The Mysterious Stranger

The Mysterious Stranger Life on the Mississippi

Life on the Mississippi Roughing It

Roughing It Alonzo Fitz and Other Stories

Alonzo Fitz and Other Stories The 30,000 Dollar Bequest and Other Stories

The 30,000 Dollar Bequest and Other Stories The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn taots-2

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn taots-2 A Double-Barreled Detective Story

A Double-Barreled Detective Story adam's diary.txt

adam's diary.txt A Horse's Tale

A Horse's Tale Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1

Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1 The Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins

The Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins Following the Equator

Following the Equator Goldsmith's Friend Abroad Again

Goldsmith's Friend Abroad Again No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger

No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger The Stolen White Elephant

The Stolen White Elephant The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories

The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories The Curious Republic of Gondour, and Other Whimsical Sketches

The Curious Republic of Gondour, and Other Whimsical Sketches Prince and the Pauper (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Prince and the Pauper (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Portable Mark Twain

The Portable Mark Twain Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Adventures of Tom Sawyer taots-1

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer taots-1 A Double Barrelled Detective Story

A Double Barrelled Detective Story Eve's Diary

Eve's Diary A Dog's Tale

A Dog's Tale The Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts (Literature)

The Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts (Literature) The Complete Short Stories of Mark Twain

The Complete Short Stories of Mark Twain What Is Man? and Other Essays

What Is Man? and Other Essays The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Zombie Jim

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Zombie Jim Who Is Mark Twain?

Who Is Mark Twain? Christian Science

Christian Science The Innocents Abroad

The Innocents Abroad Some Rambling Notes of an Idle Excursion

Some Rambling Notes of an Idle Excursion Autobiography of Mark Twain

Autobiography of Mark Twain Those Extraordinary Twins

Those Extraordinary Twins Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1

Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1