- Home

- Mark Twain

The Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts (Literature)

The Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts (Literature) Read online

by Mark Twain

Of the projected fifteen volumes of this edition of Mark Twain's previously unpublished works the following have been issued to date:

MARK TWAIN'S LETTERS TO His PUBLISHERS, 1867-1894

edited by Hamlin Hill

MARK TWAIN'S SATIRES & BURLESQUES

edited by Franklin R. Rogers

MARK TwAnv's WHICH WAS THE DREAM?

edited by John S. Tuckey

MARK TWAIN S HANNIBAL, HUCK & Tom

edited by Walter Blair

MARK TWAIN 's MYSTERIOUS STRANGER MANUSCRIPTS

edited by William M. Gibson

MARK TWAIN's CORRESPONDENCE WITH HENRY HUTTLESTON ROGERS

edited by Lewis Leary

Editorial Board

WALTER BLAIR

DONALD CONEY

HENRY NASH SMITH

Series Editor of The Mark Twain Papers

FREDERICK ANDERSON

by Mark Twain

Edited with an Introduction by

William M. Gibson

AT ONE TIME, the editors of the Iowa-California Edition of the writings of Mark Twain and the editors of The Mark Twain Papers, along with their respective publishers, intended to publish Mark Twain's Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts jointly, since the volume includes both published and unpublished writings. However, the published version is partly fraudulent, and the unpublished versions bulk larger than what had appeared in print. Moreover, the University of California Press has become the publisher for the Iowa edition (as it then was) as well as The Papers. Thus the book appears as a part of The Mark Twain Papers rather than under a double imprint.

This bit of editorial and publishing history will serve to explain my good fortune in having had two sets of editors to advise me and inspect my copy. My debt to the editorial board of The Papersto Walter Blair and Henry Nash Smith-and to the Series Editor, Frederick Anderson, is large, and I am grateful to these scholars. I also owe particular thanks to John C. Gerber and Paul Baender, editors of the Iowa-California edition, who gave me professional counsel for several years prior to the decision to place this volume in The Papers, and to John S. Tuckey, who laid the foundation for this edition in his monograph, Mark Twain and Little Satan, The Writing of The Mysterious Stranger.

It is a pleasure to record a debt of a somewhat different kind, equally real, to three former students: John A. Costello, Priscilla H. Costello, and Miriam Kotzin. Mr. and Mrs. Costello, who typed the "No. 44" narrative from photocopy of the manuscript, deciphered and bracketed into their typescript many of Mark Twain's cancellations out of their own interest in the work. Miss Kotzin did me the service of retyping and checking against photocopy my own heavily corrected typescript of Twain's working notes for the three manuscripts. I owe these young scholars thanks. I am fortunate to have had the professional help of Bernard L. Stein for more than two years and of Victor Fischer for several months in establishing cancellations and completing the textual apparatus. And I appreciate assistance in proofreading from Mariam Kagan, Bruce T. Hamilton, Theodore Guberman, and Robert Hirst.

Barbara C. Gibson, my wife, at nearly every stage in the preparation of this edition invested hours and days in verifying copy against typescript and photocopy-only she knows how many-and in helping me "break" words or phrases heavily overscored.

Finally, I am grateful to the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation for the fellowship during which I began the editorial work; and to the Office of Education, Department of Health, Education and Welfare, and the National Endowment for the Humanities for providing me with indispensable travel and research assistance. The Office of Education has been the chief supporter of the Iowa edition; the National Endowment, the chief support of The Mark Twain Papers through the Center for Editions of American Authors, Modern Language Association of America.

WILLIAM M. GIBSON

March 1968

ABBREVIATIONS

INTRODUCTION

THE TEXTS

The Chronicle of Young Satan

Schoolhouse Hill

No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger

APPENDIXES

A: Marginal Notes

B: Working Notes and Related Matter

EXPLANATORY NOTES

MARK TWAIN's The Mysterious Stranger, A Romance, as published in 1916 and reprinted since that date, is an editorial fraud perpetrated by Twain's official biographer and literary executor, Albert Bigelow Paine, and Frederick A. Duneka of Harper & Brothers publishing company. When I first read the three manuscript versions of the narrative in the Mark Twain Papers, like other scholars who had seen them, I found this dismaying conclusion to be inescapable. John S. Tuckey first demonstrated the fact in 1963 in an admirable monograph in which he dated the composition of the manuscripts;1 this publication of the texts themselves offers additional proof. Thus, half a century after a spurious version was delivered to an unsuspecting public in the form of a children's Christmas gift book, the manuscripts are presented here for the first time as they came from their author's hand.

Paine was able to publish the "final complete work"-he said in 1923-because he turned up its essential last chapter in a great batch of unfinished stories and fragments several years after Clemens died in 1910.2 On the basis of incomplete evidence and wrong dating of manuscripts, Paine's successor as literary editor, Bernard DeVoto, argued that in completing The Mysterious Stranger, Mark Twain "came back from the edge of insanity, and found as much peace as any man may find in his last years, and brought his talent into fruition and made it whole again."' Two generations of readers have found the published tale as moving as DeVoto did. Although a very few readers and critics, notably Frederick A. G. Cowper and Edwin S. Fussell,' have been troubled by inconsistencies, especially in the final chapter, most have agreed that the melancholy fable, Twain's last important fiction, formed a kind of Nunc Dimittis.

The truth is that Mark Twain attempted at least four versions of the story, which survive in three manuscripts. The Mysterious Stranger represents, partially, the first manuscript in order of composition rather than the last, as DeVoto thought. None of the three is a finished work, although Twain did draft a "Conclusion of the book" for the third manuscript with the intent-never fulfilled-of completing this last version. Further, it is now clear that Paine, aided by Duneka, cut and bowdlerized the first manuscript heavily. He borrowed the character of the astrologer from the third manuscript and attributed to the new figure the grosser acts and speeches of a priest. Then he grafted the final chapter of the third manuscript to the broken-off first manuscript version by cutting half a chapter, composing a paragraph of bridgework, and altering characters' names. Speaking of his great discovery among the confusion of papers, Paine said, "Happily, it was the ending of the story in its first form." ° Although Paine's loyalty to Mark Twain was great and his rich accumulation of data about Mark Twain's life in Mark Twain: A Biography will always be valuable, two facts must be recorded here. Ile altered the manuscript of the book in a fashion that almost certainly would have enraged Clemens, and he concealed his tampering and his grafting-on of the last chapter, presumably to create the illusion that Twain had completed the story, but never published it. One bit of evidence proves this conclusively: in the all-important final chapter, on the manuscript the names "August" and "44," which Twain had given characters in the last version, are canceled, and "Theodor" and "Satan," characters in the first version, are substituted in Paine's hand.

A case can be made for Paine. When he and Duneka lifted the magician from the third manuscript, developed this figure into the astrologer, and used him as a kind of scapegoat, they thought they were acting to sustai

n and add to Mark Twain's reputation. They cut passages that they believed would offend Catholics, Presbyterians, and others for the same reason, and in cutting they did eliminate burlesque passages that clog the story. Moreover, as the experience of thousands of readers attests, the last chapter, although it was written for another version, does fit this version remarkably well. Certain "dream-marks" do suggest a dream-conclusion. But the major and inescapable charge in the indictment of Paine as editor of The Mysterious Stranger stands-he secretly tried to fill Mark Twain's shoes, and he tampered with the faith of Mark Twain's readers.

It follows that the serial text in Harper's Monthly Magazine (May through November 1916) and the text of the book (published in late October) possess no authority in the preparation of this edition. The text of the first edition remains chiefly an exhibition of the self-confident taste of the editor and his associate, Duneka-and, it seems likely, of their desire to get out another book by "Mark Twain." One depressing aspect of their misrepre-sentational editorial work is that they commissioned N. C. Wyeth, a well-known illustrator of children's books, to illustrate their altered text, and they let the designer place a fine color engraving of that nonentity, the "borrowed" astrologer, on the front cover.

The Order of the Manuscripts

Three of Twain's holograph manuscripts in the Mark Twain Papers at the University of California in Berkeley provide the copy-text of this edition. Typescripts of the first and third manuscripts, with a few authorial corrections, possess subsidiary authority. Mark Twain's titles for each, in the order of composition, were "The Chronicle of Young Satan," "Schoolhouse Hill," and "No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger." His manuscript workingnotes for the three versions, a long notebook entry about "little Satan, jr.," and a single discarded page of manuscript surviving from revision are included entire in appendixes. Explanatory notes follow.'The Textual Apparatus describes the texts, sets forth the editorial principles observed, lists the recovered cancellations, and gives all editorial choices or emendations. Here, as elsewhere in the University of California Press edition of The Mark Twain Papers, the intention is to set forth all the evidence for the making of the text.

The present dating of these works follows closely the conclusions of Tuckey, who in Mark Twain and Little Satan made a thorough examination not only of the manuscripts but of the whole body of documents in the Mark Twain Papers from 1897 through 1908, comparing papers, inks, and handwriting for dating clues and making skilled use of internal evidence as well.' Other literary evidence to be cited supports Tuckey's dating at every point.

Four versions of the narrative are to be distinguished in the three manuscripts:

Version A. The first may be called the "St. Petersburg Fragment" (Tuckey's "Pre-Eseldorf" pages). It consists of nineteen manuscript pages preserved from a version of the story which was set in St. Petersburg. They were written after Mark Twain's arrival in Vienna in late September 1897 and were revised and worked into the early part of Version B. A number of canceled references to St. Petersburg identify the original setting. For black walnuts (which are Missouri trees) Twain later substituted chestnuts, for dollars he later substituted ducats, and for the village bank he wrote in the name of Solomon Isaacs, the moneylender. He substituted Nikolaus for Huck, Theodor for George (Tom in the notes), Father Peter for Mr. Black, Seppi for Pole, and Wilhelm Meidling for Tom Andrews "of good Kentucky stock." References that placed the story in the 1840's of the author's boyhood were deleted. The action includes Satan's lecture on the Moral Sense, Mr. Black's finding of the dollars, and the stir this discovery makes in the village.

Version B. "The Chronicle of Young Satan" ("Eseldorf," as DeVoto referred to it) is Mark Twain's own title for a story of some 423 manuscript pages which breaks off in mid-chapter in the court of an Indian rajah, where Satan is competing with the court magician. The main setting is Eseldorf, an Austrian village, in 1702; the action begins in May. The chief characters are the narrator Theodor Fischer and his youthful companions Seppi Wohlmeyer and Nikolaus Baumann; Father Peter and Father Adolf, the good and evil priests; Marget, the niece of Father Peter, and Ursula, their servant; Wilhelm Meidling, Marget's suitor; Lisa Brandt and her mother. Finally there is the stranger, known to the villagers as Philip Traum, although at home he is called Satan, after his uncle.

Mark Twain wrote "Chronicle" in three periods between November 1897 and September 1900, not long before he returned to the United States from Europe, free from his "long nightmare" of debt. In the first period from November 1897 through January 1898 in Vienna, Twain reworked the "St. Petersburg Fragment" into a plot sequence which develops the character of Father Adolf and then tells of the boys' first encounter with Satan, Father Peter's trial on the charge of stealing Father Adolf's gold, and Father Peter's vindication.' Twain concluded in the following months, however, that he had resolved the conflict between the priests too rapidly, and apparently he decided that for Satan to drive Father Peter into a state of "happy insanity" at the very moment when the old man was proved innocent would provide the true ending he was seeking. So, returning to his manuscript between May and October 1899, Twain put aside the trial scene and developed further episodes, mixing into them Socratic dialogues on the workings of the Moral Sense.' Theodor recalls the story of the girls burned as witches because of fleabite "signs" and tells how Gottfried Narr's grandmother had suffered the same fate in their village.' The village is forced to choose between charging Father Adolf with witchcraft and suffering an Interdict. Fuchs and Meidling suffer pangs of jealousy because Lilly Fischer and Marget become infatuated with Satan and his knowledge and creative skills. This spurt of sustained composition ended approximately with Twain's summary passage early in chapter 6:

What a lot of dismal haps had befallen the village, and certainly Satan seemed to be the father of the whole of them: Father Peter in prison . . . Marget's household shunned . . . Father Adolf acquiring a frightful and odious reputation . . . my parents worried ... Joseph crushed . . . Wilhelm's heart broken . . . Marget gone silly, and our Lilly following after; the whole village prodded and pestered into a pathetic delirium about nonexistent witches . . . the whole wide wreck and desolation . . . the work of Satan's enthusiastic diligence and morbid passion for business.

Twain wrote the remaining half of "Chronicle" from June through August 1900, in London and at nearby Dollis Hill. His hatred of cruelty (which would lead him to begin a book about lynchings in the United States) continued to manifest itself in passages that showed the burning of Frau Brandt at the stake for blasphemy, the punishment of the gamekeepers, Theodor 's presence at the pressing to death of a gentlewoman in Scotland, and the Eseldorf mob's stoning and hanging of the "born lady."

Satan's freedom in time and space and his godlike powers also make possible two new strands of action: he changes the lives of Nick and Lisa to bring on their drowning, and he refers to future -that is, contemporary-events. In the spring and summer of 1900, Clemens was increasingly angered by the role of the European powers in the Boxer Rebellion; and, despite his admiration for the British and their institutions, he became increasingly committed to the cause of the Boer Republics. Satan refers sardonically to both situations in chapters 6 and 8.

Nearly all the episodes thus far lead to the deferred episode wherein Father Peter is exonerated and goes mad, the conclusion toward which Twain presumably had been working. But the pressure of world events and Twain's sense that he probably would not publish this book in his lifetime carried him on. King Humbert the Good of Italy was assassinated by an anarchist at Monza on 29 July 1900 and died excommunicated. Pope Leo XIII subsequently forbade priests to recite a "tender prayer" composed by Queen Margherita that already had been widely repeated in Italy and the Catholic world. Twain must almost at once have seized upon this as "proof" of the doctrine of papal infallibility.10 His version of the event probably inspired the famous generalization on the power of laughter-and the failure of the human race to make use of its one great weapon. Then Twain ad

ded a parable on the price the British might have to pay for their tenure in India; and the Indian setting inspired him to begin another "adventure" of Satan and Theodor in the court of a rajah. At this point the manuscript ends.

Version C. "Schoolhouse Hill," or the Hannibal version, a fragment of 16,000 words, is first adumbrated in Mark Twain's notebook in November 1898. His entry begins:

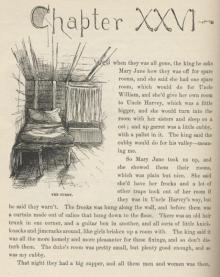

Story of little Satan, jr, who came to (Petersburg (Hannibal)) went to school, was popular and greatly liked by (Huck and Tom) who knew his secret. The others were jealous, and the girls didn't like him because he smelt of brimstone. This is the Admirable Crichton He was always doing miracles-his pals knew they were miracles, the(y) others thought them mysteries. He is a good little devil; but swears, and breaks the Sabbath. By and by he is converted, and becomes a Methodist. and quits miracling. . . . As he does no more miracles, even his pals(s) fall away and disbelieve in him. When his fortunes and his miseries are at the worst, his papa arrives in state in a glory of hellfire and attended by a multitude of old-fashioned and showy fiends-and then everybody is at the boy-devil's feet at once and want to curry favor.

Little Satan, Jr., is also to perform tricks at jugglery shows, to try to win Mississippi raftsmen to Christ, and to take Tom and Huck to stay with him over Sunday in hell.11 The complete entry, with Mark Twain's working notes, shows that for the moment he had put the trial sequence of "Chronicle" aside and was making a fresh start in a mood of comedy. Whereas "Chronicle" is the first-person narrative of young Fischer, the six chapters of November and December 1898 are told by an omniscient narrator. Apparently, it was to be both an essay in the correction of ideas and a comedy set in the world of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, whose boyhero would like to reform and save it.

The miraculous boy, now renamed 44, appears one winter morning in the St. Petersburg school and performs marvels by reading books at a glance and learning languages in minutes. With Tom and Huck on his side, he fights and puts down the school bully. The Hotchkiss family take him into their home, where he feeds and talks to the savage family cat. And, after saving Crazy Meadows and others from a blinding blizzard, he appears miraculously at a seance. Here the manuscript ends.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 1.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 1. The Prince and the Pauper

The Prince and the Pauper The American Claimant

The American Claimant Eve's Diary, Complete

Eve's Diary, Complete Extracts from Adam's Diary, translated from the original ms.

Extracts from Adam's Diary, translated from the original ms. A Tramp Abroad

A Tramp Abroad The Best Short Works of Mark Twain

The Best Short Works of Mark Twain Humorous Hits and How to Hold an Audience

Humorous Hits and How to Hold an Audience The Speculative Fiction of Mark Twain

The Speculative Fiction of Mark Twain The Facts Concerning the Recent Carnival of Crime in Connecticut

The Facts Concerning the Recent Carnival of Crime in Connecticut Alonzo Fitz, and Other Stories

Alonzo Fitz, and Other Stories The $30,000 Bequest, and Other Stories

The $30,000 Bequest, and Other Stories Pudd'nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins

Pudd'nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the Undead

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the Undead Sketches New and Old

Sketches New and Old The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg

The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg A Tramp Abroad — Volume 06

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 06 A Tramp Abroad — Volume 02

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 02 The Prince and the Pauper, Part 1.

The Prince and the Pauper, Part 1. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 16 to 20

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 16 to 20 The Prince and the Pauper, Part 9.

The Prince and the Pauper, Part 9. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 21 to 25

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 21 to 25 Tom Sawyer, Detective

Tom Sawyer, Detective A Tramp Abroad (Penguin ed.)

A Tramp Abroad (Penguin ed.) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 36 to the Last

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 36 to the Last The Mysterious Stranger, and Other Stories

The Mysterious Stranger, and Other Stories A Tramp Abroad — Volume 03

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 03 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 3.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 3. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 06 to 10

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 06 to 10_preview.jpg) The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade)

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 31 to 35

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 31 to 35 The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg, and Other Stories

The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg, and Other Stories A Tramp Abroad — Volume 07

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 07 Editorial Wild Oats

Editorial Wild Oats Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 26 to 30

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 26 to 30 1601: Conversation as it was by the Social Fireside in the Time of the Tudors

1601: Conversation as it was by the Social Fireside in the Time of the Tudors A Tramp Abroad — Volume 05

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 05 Sketches New and Old, Part 1.

Sketches New and Old, Part 1. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 2.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 2. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 8.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 8. A Tramp Abroad — Volume 01

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 01 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 5.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 5. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 01 to 05

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 01 to 05 A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 1.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 1. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 4.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 4. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 2.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 2. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 7.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 7. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 3.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 3. Sketches New and Old, Part 4.

Sketches New and Old, Part 4. Sketches New and Old, Part 3.

Sketches New and Old, Part 3. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 7.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 7. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 5.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 5. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 6.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 6. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 4.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 4. Sketches New and Old, Part 2.

Sketches New and Old, Part 2. Sketches New and Old, Part 6.

Sketches New and Old, Part 6. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 11 to 15

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 11 to 15 Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc

Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc Sketches New and Old, Part 5.

Sketches New and Old, Part 5. Eve's Diary, Part 3

Eve's Diary, Part 3 Sketches New and Old, Part 7.

Sketches New and Old, Part 7. Mark Twain on Religion: What Is Man, the War Prayer, Thou Shalt Not Kill, the Fly, Letters From the Earth

Mark Twain on Religion: What Is Man, the War Prayer, Thou Shalt Not Kill, the Fly, Letters From the Earth Tales, Speeches, Essays, and Sketches

Tales, Speeches, Essays, and Sketches A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 9.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 9. Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands (version 1)

Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands (version 1) 1601

1601 Letters from the Earth

Letters from the Earth Curious Republic Of Gondour, And Other Curious Whimsical Sketches

Curious Republic Of Gondour, And Other Curious Whimsical Sketches The Mysterious Stranger

The Mysterious Stranger Life on the Mississippi

Life on the Mississippi Roughing It

Roughing It Alonzo Fitz and Other Stories

Alonzo Fitz and Other Stories The 30,000 Dollar Bequest and Other Stories

The 30,000 Dollar Bequest and Other Stories The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn taots-2

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn taots-2 A Double-Barreled Detective Story

A Double-Barreled Detective Story adam's diary.txt

adam's diary.txt A Horse's Tale

A Horse's Tale Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1

Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1 The Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins

The Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins Following the Equator

Following the Equator Goldsmith's Friend Abroad Again

Goldsmith's Friend Abroad Again No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger

No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger The Stolen White Elephant

The Stolen White Elephant The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories

The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories The Curious Republic of Gondour, and Other Whimsical Sketches

The Curious Republic of Gondour, and Other Whimsical Sketches Prince and the Pauper (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Prince and the Pauper (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Portable Mark Twain

The Portable Mark Twain Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Adventures of Tom Sawyer taots-1

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer taots-1 A Double Barrelled Detective Story

A Double Barrelled Detective Story Eve's Diary

Eve's Diary A Dog's Tale

A Dog's Tale The Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts (Literature)

The Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts (Literature) The Complete Short Stories of Mark Twain

The Complete Short Stories of Mark Twain What Is Man? and Other Essays

What Is Man? and Other Essays The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Zombie Jim

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Zombie Jim Who Is Mark Twain?

Who Is Mark Twain? Christian Science

Christian Science The Innocents Abroad

The Innocents Abroad Some Rambling Notes of an Idle Excursion

Some Rambling Notes of an Idle Excursion Autobiography of Mark Twain

Autobiography of Mark Twain Those Extraordinary Twins

Those Extraordinary Twins Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1

Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1