- Home

- Mark Twain

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 7.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 7. Read online

Produced by David Widger

A CONNECTICUT YANKEE IN KING ARTHUR'S COURT

by

MARK TWAIN (Samuel L. Clemens)

Part 7.

CHAPTER XXXII

DOWLEY'S HUMILIATION

Well, when that cargo arrived toward sunset, Saturday afternoon,I had my hands full to keep the Marcos from fainting. They weresure Jones and I were ruined past help, and they blamed themselvesas accessories to this bankruptcy. You see, in addition to thedinner-materials, which called for a sufficiently round sum,I had bought a lot of extras for the future comfort of the family:for instance, a big lot of wheat, a delicacy as rare to the tablesof their class as was ice-cream to a hermit's; also a sizeabledeal dinner-table; also two entire pounds of salt, which wasanother piece of extravagance in those people's eyes; also crockery,stools, the clothes, a small cask of beer, and so on. I instructedthe Marcos to keep quiet about this sumptuousness, so as to giveme a chance to surprise the guests and show off a little. Concerningthe new clothes, the simple couple were like children; they were upand down, all night, to see if it wasn't nearly daylight, so thatthey could put them on, and they were into them at last as muchas an hour before dawn was due. Then their pleasure--not to saydelirium--was so fresh and novel and inspiring that the sight of itpaid me well for the interruptions which my sleep had suffered.The king had slept just as usual--like the dead. The Marcos couldnot thank him for their clothes, that being forbidden; but theytried every way they could think of to make him see how gratefulthey were. Which all went for nothing: he didn't notice any change.

It turned out to be one of those rich and rare fall days which isjust a June day toned down to a degree where it is heaven to beout of doors. Toward noon the guests arrived, and we assembledunder a great tree and were soon as sociable as old acquaintances.Even the king's reserve melted a little, though it was some littletrouble to him to adjust himself to the name of Jones along atfirst. I had asked him to try to not forget that he was a farmer;but I had also considered it prudent to ask him to let the thingstand at that, and not elaborate it any. Because he was just thekind of person you could depend on to spoil a little thing likethat if you didn't warn him, his tongue was so handy, and hisspirit so willing, and his information so uncertain.

Dowley was in fine feather, and I early got him started, and thenadroitly worked him around onto his own history for a text andhimself for a hero, and then it was good to sit there and hear himhum. Self-made man, you know. They know how to talk. They dodeserve more credit than any other breed of men, yes, that is true;and they are among the very first to find it out, too. He told howhe had begun life an orphan lad without money and without friendsable to help him; how he had lived as the slaves of the meanestmaster lived; how his day's work was from sixteen to eighteen hourslong, and yielded him only enough black bread to keep him in ahalf-fed condition; how his faithful endeavors finally attractedthe attention of a good blacksmith, who came near knocking himdead with kindness by suddenly offering, when he was totallyunprepared, to take him as his bound apprentice for nine yearsand give him board and clothes and teach him the trade--or "mystery"as Dowley called it. That was his first great rise, his firstgorgeous stroke of fortune; and you saw that he couldn't yet speakof it without a sort of eloquent wonder and delight that such agilded promotion should have fallen to the lot of a common humanbeing. He got no new clothing during his apprenticeship, but onhis graduation day his master tricked him out in spang-new tow-linensand made him feel unspeakably rich and fine.

"I remember me of that day!" the wheelwright sang out, withenthusiasm.

"And I likewise!" cried the mason. "I would not believe theywere thine own; in faith I could not."

"Nor other!" shouted Dowley, with sparkling eyes. "I was liketo lose my character, the neighbors wending I had mayhap beenstealing. It was a great day, a great day; one forgetteth notdays like that."

Yes, and his master was a fine man, and prosperous, and alwayshad a great feast of meat twice in the year, and with it whitebread, true wheaten bread; in fact, lived like a lord, so to speak.And in time Dowley succeeded to the business and married the daughter.

"And now consider what is come to pass," said he, impressively."Two times in every month there is fresh meat upon my table."He made a pause here, to let that fact sink home, then added--"and eight times salt meat."

"It is even true," said the wheelwright, with bated breath.

"I know it of mine own knowledge," said the mason, in the samereverent fashion.

"On my table appeareth white bread every Sunday in the year,"added the master smith, with solemnity. "I leave it to your ownconsciences, friends, if this is not also true?"

"By my head, yes," cried the mason.

"I can testify it--and I do," said the wheelwright.

"And as to furniture, ye shall say yourselves what mine equipmentis." He waved his hand in fine gesture of granting frank andunhampered freedom of speech, and added: "Speak as ye are moved;speak as ye would speak; an I were not here."

"Ye have five stools, and of the sweetest workmanship at that, albeityour family is but three," said the wheelwright, with deep respect.

"And six wooden goblets, and six platters of wood and two of pewterto eat and drink from withal," said the mason, impressively. "AndI say it as knowing God is my judge, and we tarry not here alway,but must answer at the last day for the things said in the body,be they false or be they sooth."

"Now ye know what manner of man I am, brother Jones," said thesmith, with a fine and friendly condescension, "and doubtless yewould look to find me a man jealous of his due of respect andbut sparing of outgo to strangers till their rating and quality beassured, but trouble yourself not, as concerning that; wit ye wellye shall find me a man that regardeth not these matters but iswilling to receive any he as his fellow and equal that carrietha right heart in his body, be his worldly estate howsoever modest.And in token of it, here is my hand; and I say with my own mouthwe are equals--equals"--and he smiled around on the company withthe satisfaction of a god who is doing the handsome and graciousthing and is quite well aware of it.

The king took the hand with a poorly disguised reluctance, andlet go of it as willingly as a lady lets go of a fish; all of whichhad a good effect, for it was mistaken for an embarrassment naturalto one who was being called upon by greatness.

The dame brought out the table now, and set it under the tree.It caused a visible stir of surprise, it being brand new and asumptuous article of deal. But the surprise rose higher stillwhen the dame, with a body oozing easy indifference at every pore,but eyes that gave it all away by absolutely flaming with vanity,slowly unfolded an actual simon-pure tablecloth and spread it.That was a notch above even the blacksmith's domestic grandeurs,and it hit him hard; you could see it. But Marco was in Paradise;you could see that, too. Then the dame brought two fine newstools--whew! that was a sensation; it was visible in the eyes ofevery guest. Then she brought two more--as calmly as she could.Sensation again--with awed murmurs. Again she brought two--walking on air, she was so proud. The guests were petrified, andthe mason muttered:

"There is that about earthly pomps which doth ever move to reverence."

As the dame turned away, Marco couldn't help slapping on the climaxwhile the thing was hot; so he said with what was meant for alanguid composure but was a poor imitation of it:

"These suffice; leave the rest."

So there were more yet! It was a fine effect. I couldn't haveplayed the hand better myself.

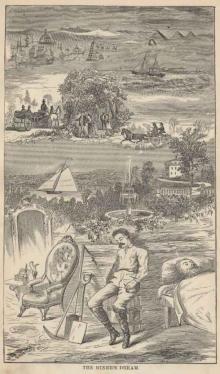

>

From this out, the madam piled up the surprises with a rush thatfired the general astonishment up to a hundred and fifty in theshade, and at the same time paralyzed expression of it down togasped "Oh's" and "Ah's," and mute upliftings of hands and eyes.She fetched crockery--new, and plenty of it; new wooden gobletsand other table furniture; and beer, fish, chicken, a goose, eggs,roast beef, roast mutton, a ham, a small roast pig, and a wealthof genuine white wheaten bread. Take it by and large, that spreadlaid everything far and away in the shade that ever that crowd hadseen before. And while they sat there just simply stupefied withwonder and awe, I sort of waved my hand as if by accident, andthe storekeeper's son emerged from space and said he had cometo collect.

"That's all right," I said, indifferently. "What is the amount?give us the items."

Then he read off this bill, while those three amazed men listened,and serene waves of satisfaction rolled over my soul and alternatewaves of terror and admiration surged over Marco's:

2 pounds salt . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 200 8 dozen pints beer, in the wood . . . . . 800 3 bushels wheat . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2,700 2 pounds fish . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100 3 hens . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 400 1 goose . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 400 3 dozen eggs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 150 1 roast of beef . . . . . . . . . . . . . 450 1 roast of mutton . . . . . . . . . . . . 400 1 ham . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 800 1 sucking pig . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 500 2 crockery dinner sets . . . . . . . . . 6,000 2 men's suits and underwear . . . . . . . 2,800 1 stuff and 1 linsey-woolsey gown and underwear . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1,600 8 wooden goblets . . . . . . . . . . . . 800 Various table furniture . . . . . . . . .10,000 1 deal table . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3,000 8 stools . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4,000 2 miller guns, loaded . . . . . . . . . . 3,000

He ceased. There was a pale and awful silence. Not a limb stirred.Not a nostril betrayed the passage of breath.

"Is that all?" I asked, in a voice of the most perfect calmness.

"All, fair sir, save that certain matters of light moment areplaced together under a head hight sundries. If it would likeyou, I will sepa--"

"It is of no consequence," I said, accompanying the words witha gesture of the most utter indifference; "give me the grandtotal, please."

The clerk leaned against the tree to stay himself, and said:

"Thirty-nine thousand one hundred and fifty milrays!"

The wheelwright fell off his stool, the others grabbed the tableto save themselves, and there was a deep and general ejaculation of:

"God be with us in the day of disaster!"

The clerk hastened to say:

"My father chargeth me to say he cannot honorably require youto pay it all at this time, and therefore only prayeth you--"

I paid no more heed than if it were the idle breeze, but, with anair of indifference amounting almost to weariness, got out my moneyand tossed four dollars on to the table. Ah, you should have seenthem stare!

The clerk was astonished and charmed. He asked me to retainone of the dollars as security, until he could go to town and--I interrupted:

"What, and fetch back nine cents? Nonsense! Take the whole.Keep the change."

There was an amazed murmur to this effect:

"Verily this being is _made_ of money! He throweth it away evenas if it were dirt."

The blacksmith was a crushed man.

The clerk took his money and reeled away drunk with fortune. I saidto Marco and his wife:

"Good folk, here is a little trifle for you"--handing the miller-gunsas if it were a matter of no consequence, though each of themcontained fifteen cents in solid cash; and while the poor creatureswent to pieces with astonishment and gratitude, I turned to theothers and said as calmly as one would ask the time of day:

"Well, if we are all ready, I judge the dinner is. Come, fall to."

Ah, well, it was immense; yes, it was a daisy. I don't know thatI ever put a situation together better, or got happier spectaculareffects out of the materials available. The blacksmith--well, hewas simply mashed. Land! I wouldn't have felt what that man wasfeeling, for anything in the world. Here he had been blowing andbragging about his grand meat-feast twice a year, and his freshmeat twice a month, and his salt meat twice a week, and his whitebread every Sunday the year round--all for a family of three; theentire cost for the year not above 69.2.6 (sixty-nine cents, twomills and six milrays), and all of a sudden here comes along a manwho slashes out nearly four dollars on a single blow-out; and notonly that, but acts as if it made him tired to handle such smallsums. Yes, Dowley was a good deal wilted, and shrunk-up andcollapsed; he had the aspect of a bladder-balloon that's beenstepped on by a cow.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 1.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 1. The Prince and the Pauper

The Prince and the Pauper The American Claimant

The American Claimant Eve's Diary, Complete

Eve's Diary, Complete Extracts from Adam's Diary, translated from the original ms.

Extracts from Adam's Diary, translated from the original ms. A Tramp Abroad

A Tramp Abroad The Best Short Works of Mark Twain

The Best Short Works of Mark Twain Humorous Hits and How to Hold an Audience

Humorous Hits and How to Hold an Audience The Speculative Fiction of Mark Twain

The Speculative Fiction of Mark Twain The Facts Concerning the Recent Carnival of Crime in Connecticut

The Facts Concerning the Recent Carnival of Crime in Connecticut Alonzo Fitz, and Other Stories

Alonzo Fitz, and Other Stories The $30,000 Bequest, and Other Stories

The $30,000 Bequest, and Other Stories Pudd'nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins

Pudd'nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the Undead

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the Undead Sketches New and Old

Sketches New and Old The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg

The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg A Tramp Abroad — Volume 06

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 06 A Tramp Abroad — Volume 02

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 02 The Prince and the Pauper, Part 1.

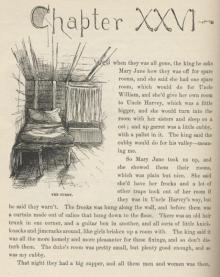

The Prince and the Pauper, Part 1. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 16 to 20

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 16 to 20 The Prince and the Pauper, Part 9.

The Prince and the Pauper, Part 9. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 21 to 25

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 21 to 25 Tom Sawyer, Detective

Tom Sawyer, Detective A Tramp Abroad (Penguin ed.)

A Tramp Abroad (Penguin ed.) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 36 to the Last

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 36 to the Last The Mysterious Stranger, and Other Stories

The Mysterious Stranger, and Other Stories A Tramp Abroad — Volume 03

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 03 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 3.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 3. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 06 to 10

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 06 to 10_preview.jpg) The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade)

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 31 to 35

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 31 to 35 The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg, and Other Stories

The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg, and Other Stories A Tramp Abroad — Volume 07

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 07 Editorial Wild Oats

Editorial Wild Oats Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 26 to 30

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 26 to 30 1601: Conversation as it was by the Social Fireside in the Time of the Tudors

1601: Conversation as it was by the Social Fireside in the Time of the Tudors A Tramp Abroad — Volume 05

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 05 Sketches New and Old, Part 1.

Sketches New and Old, Part 1. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 2.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 2. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 8.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 8. A Tramp Abroad — Volume 01

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 01 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 5.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 5. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 01 to 05

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 01 to 05 A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 1.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 1. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 4.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 4. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 2.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 2. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 7.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 7. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 3.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 3. Sketches New and Old, Part 4.

Sketches New and Old, Part 4. Sketches New and Old, Part 3.

Sketches New and Old, Part 3. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 7.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 7. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 5.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 5. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 6.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 6. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 4.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 4. Sketches New and Old, Part 2.

Sketches New and Old, Part 2. Sketches New and Old, Part 6.

Sketches New and Old, Part 6. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 11 to 15

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 11 to 15 Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc

Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc Sketches New and Old, Part 5.

Sketches New and Old, Part 5. Eve's Diary, Part 3

Eve's Diary, Part 3 Sketches New and Old, Part 7.

Sketches New and Old, Part 7. Mark Twain on Religion: What Is Man, the War Prayer, Thou Shalt Not Kill, the Fly, Letters From the Earth

Mark Twain on Religion: What Is Man, the War Prayer, Thou Shalt Not Kill, the Fly, Letters From the Earth Tales, Speeches, Essays, and Sketches

Tales, Speeches, Essays, and Sketches A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 9.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 9. Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands (version 1)

Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands (version 1) 1601

1601 Letters from the Earth

Letters from the Earth Curious Republic Of Gondour, And Other Curious Whimsical Sketches

Curious Republic Of Gondour, And Other Curious Whimsical Sketches The Mysterious Stranger

The Mysterious Stranger Life on the Mississippi

Life on the Mississippi Roughing It

Roughing It Alonzo Fitz and Other Stories

Alonzo Fitz and Other Stories The 30,000 Dollar Bequest and Other Stories

The 30,000 Dollar Bequest and Other Stories The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn taots-2

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn taots-2 A Double-Barreled Detective Story

A Double-Barreled Detective Story adam's diary.txt

adam's diary.txt A Horse's Tale

A Horse's Tale Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1

Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1 The Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins

The Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins Following the Equator

Following the Equator Goldsmith's Friend Abroad Again

Goldsmith's Friend Abroad Again No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger

No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger The Stolen White Elephant

The Stolen White Elephant The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories

The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories The Curious Republic of Gondour, and Other Whimsical Sketches

The Curious Republic of Gondour, and Other Whimsical Sketches Prince and the Pauper (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Prince and the Pauper (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Portable Mark Twain

The Portable Mark Twain Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Adventures of Tom Sawyer taots-1

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer taots-1 A Double Barrelled Detective Story

A Double Barrelled Detective Story Eve's Diary

Eve's Diary A Dog's Tale

A Dog's Tale The Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts (Literature)

The Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts (Literature) The Complete Short Stories of Mark Twain

The Complete Short Stories of Mark Twain What Is Man? and Other Essays

What Is Man? and Other Essays The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Zombie Jim

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Zombie Jim Who Is Mark Twain?

Who Is Mark Twain? Christian Science

Christian Science The Innocents Abroad

The Innocents Abroad Some Rambling Notes of an Idle Excursion

Some Rambling Notes of an Idle Excursion Autobiography of Mark Twain

Autobiography of Mark Twain Those Extraordinary Twins

Those Extraordinary Twins Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1

Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1