- Home

- Mark Twain

Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1 Page 11

Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1 Read online

Page 11

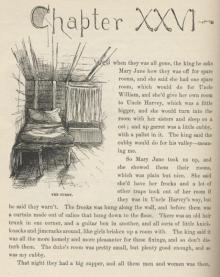

“It ain’t no use: Bob can’t climb up to that!”

During the next hour he held his position against the wall in a sort of dazed abstraction, apparently unconscious of place or of anything else, and at last when Ingersoll mounted the supper table his worshipper merely straightened up to an attitude of attention but without manifesting any hope.

Ingersoll with his fair and fresh complexion, handsome figure and graceful carriage was beautiful to look at.

He was to respond to the toast of “The Volunteers,” and his first sentence or two showed his quality. As his third sentence fell from his lips the house let go with a crash, and my private looked pleased and for the first time hopeful but he had been too much frightened to join in the applause. Presently, when Ingersoll came to the passage in which he said that these volunteers had shed their blood and perilled their lives in order that a mother might own her own child, the language was so fine, whatever it was, for I have forgotten, and the delivery was so superb that the vast multitude rose as one man and stood on their feet, shouting, stamping, and filling all the place with such a waving of napkins that it was like a snow storm. This prodigious outburst continued for a minute or two, Ingersoll standing and waiting. And now I happened to notice my private. He was stamping, clapping, shouting, gesticulating like a man who had gone truly mad. At last when quiet was restored once more, he glanced up to me with the tears in his eyes and said:

“Egod! He didn’t get left!”

My own speech was granted the perilous distinction of the place of honor. It was the last speech on the list, an honor which no person, probably, has ever sought. It was not reached until two o’clock in the morning. But when I got on my feet I knew that there was at any rate one point in my favor: the text was bound to have the sympathy of nine-tenths of the men present and of every woman, married or single, of the crowds of the sex who stood huddled in the various doorways.

I expected the speech to go off well—and it did.

In it I had a drive at General Sheridan’s comparatively new twins and various other things calculated to make it go. There was only one thing in it that I had fears about, and that one thing stood where it could not be removed in case of disaster.

It was the last sentence in the speech.

I had been picturing the America of fifty years hence, with a population of two hundred million souls, and was saying that the future President, Admirals and so forth of that great coming time were now lying in their various cradles, scattered abroad over the vast expanse of this country, and then said “And now in his cradle somewhere under the flag the future illustrious Commander-in-Chief of the American armies is so little burdened with his approaching grandeur and responsibilities as to be giving his whole strategic mind at this moment to trying to find out some way to get his big toe into his mouth—something, meaning no disrespect to the illustrious guest of this evening, which he turned his entire attention to some fifty-six years ago”—

And here, as I had expected, the laughter ceased and a sort of shuddering silence took its place—for this was apparently carrying the matter too far.

I waited a moment or two to let this silence sink well home.

Then, turning toward the General I added:

“And if the child is but the father of the man there are mighty few who will doubt that he succeeded.”

Which relieved the house: for when they saw the General break up in good-sized pieces they followed suit with great enthusiasm.

[A Call with W. D. Howells on General Grant]

Howells

1881.

Howells wrote me that his old father, who is well along in the seventies, was in great distress about his poor little consulate, up in Quebec. Somebody not being satisfied with the degree of poverty already conferred upon him by a thoughtful and beneficent Providence, was anxious to add to it by acquiring the Quebec consulate. So Howells thought that if we could get General Grant to say a word to President Arthur it might have the effect of stopping this effort to oust old Mr. Howells from his position. Therefore, at my suggestion Howells came down and we went to New York to lay the matter before the General. We found him at number 2, Wall street, in the principal office of Grant and Ward, brokers.

I stated the case and asked him if he wouldn’t write a word on a card which Howells could carry to Washington and hand to the President.

But, as usual, General Grant was his natural self—that is to say, ready and also determined to do a great deal more for you than you could possibly have the effrontery to ask him to do. Apparently he never meets anybody half way: he comes nine-tenths of the way himself voluntarily. “No” he said,—he would do better than that and cheerfully: he was going to Washington in a couple of days to dine with the President and he would speak to him himself and make it a personal matter. Now as General Grant not only never forgets a promise but never even the shadow of a promise, he did as he said he would do, and within a week came a letter from the Secretary of State, Mr. Frelinghuysen, to say that in no case would old Mr. Howells be disturbed. [And he wasn’t. He resigned, a couple of years later.]

1881.

But to go back to the interview with General Grant, he was in a humor to talk—in fact he was always in a humor to talk when no strangers were present—and he resisted all our efforts to leave him.

He forced us to stay and take luncheon in a private room and continued to talk all the time. [It was bacon and beans. Nevertheless, “How he sits and towers”—Howells, quoting from Dante.]

He remembered “Squibob” Derby at West Point very well. He said that Derby was forever drawing caricatures of the professors and playing jokes of all kinds on everybody. He also told of one thing, which I had heard before, but which I have never seen in print. At West Point, the professor was instructing and questioning a class concerning certain particulars of a possible siege and he said this, as nearly as I can remember: I cannot quote General Grant’s words:

Given: That a thousand men are besieging a fortress whose equipment of men, provisions, etc., are so and so—it is a military axiom that at the end of forty-five days the fort will surrender. Now, young men, if any of you were in command of such a fortress, how would you proceed?

Derby held up his hand in token that he had an answer for that question. He said: “I would march out, let the enemy in, and at the end of forty-five days I would change places with him.”

Grant’s Memoirs

1881.

I tried very hard to get General Grant to write his personal memoirs for publication but he would not listen to the suggestion. His inborn diffidence made him shrink from voluntarily coming forward before the public and placing himself under criticism as an author. He had no confidence in his ability to write well, whereas I and everybody else in the world excepting himself are aware that he possesses an admirable literary gift and style. He was also sure that the book would have no sale and of course that would be a humiliation, too. He instanced the fact that General Badeau’s military history of General Grant had had but a trifling sale, and that John Russell Young’s account of General Grant’s trip around the globe had hardly any sale at all. But I said that these were not instances in point; that what another man might tell about General Grant was nothing, while what General Grant should tell about himself with his own pen was a totally different thing. I said that the book would have an enormous sale: that it should be in two volumes sold in cash at $3 50 apiece, and that the sale in two volumes would certainly reach half a million sets. I said that from my experience I could save him from making unwise contracts with publishers and could also suggest the best plan of publication—the subscription plan—and find for him the best men in that line of business.

I had in my mind at that time the American Publishing Company of Hartford, and while I suspected that they had been swindling me for ten years I was well aware that I could arrange the contract in such a way that they could not swindle General Grant. But the General said that he had no necessity for an

y addition to his income. I knew that he meant by that that his investments through the firm in which his sons were partners were paying him all the money he needed. So I was not able to persuade him to write a book. He said that some day he would make very full notes and leave them behind him and then if his children chose to make them into a book that would answer.

Grant and the Chinese

1884.

Early in this year or late in 1883, if my memory serves me, I called on General Grant with Yung Wing, late Chinese Minister at Washington, to introduce Wing and let him lay before General Grant a proposition. Li-Hung-Chang, one of the greatest and most progressive men in China since the death of Prince Kung, had been trying to persuade the Imperial government to build a system of military railroads in China, and had so far succeeded in his persuasions that a majority of the government were willing to consider the matter—provided that money could be obtained for that purpose, outside of China—this money to be raised upon the customs of the country and by bonding the railway or some such way. Yung Wing believed that if General Grant would take charge of the matter here and create the syndicate the money would be easily forthcoming. He also knew that General Grant was better and more favorably known in China than any other foreigner in the world and was aware that if his name were associated with the enterprise—the syndicate—it would inspire the Chinese government and people and give them the greatest possible sense of security. We found the General cooped up in his room with a severe rheumatism resulting from a fall on the ice, which he had got some months before. He would not undertake a syndicate, because times were so hard here that people would be loath to invest money so far away. Of course Yung Wing’s proposal included a liberal compensation for General Grant for his trouble, but that was a thing that the General would not listen to for a moment. He said that easier times would come by and bye, and that the money could then be raised, no doubt, and that he would enter into it cheerfully and with zeal and carry it through to the very best of his ability, but he must do it without compensation. In no case would he consent to take any money for it. Here again he manifested the very strongest interest in China, an interest which I had seen him evince on previous occasions. He said he had urged a system of railways on Li-Hung-Chang when he was in China and he now felt so sure that such a system would be a great salvation for the country and also the beginning of the country’s liberation from the Tartar rule and thraldom that he would be quite willing at a favorable time to do everything he could toward carrying out that project without other compensation than the pleasure he would derive from being useful to China.

This reminds me of one other circumstance.

About 1879 or 1880, the Chinese pupils in Hartford and other New England towns had been ordered home by the Chinese government. There were two parties in the Chinese government: one headed by Li-Hung-Chang, the progressive party, which was striving to introduce Western arts and education into China, and the other was opposed to all progressive measures. Li-Hung-Chang and the progressive party kept the upper hand for some time and during this period the government had sent one hundred or more of the country’s choicest youth over here to be educated. But now the other party had got the upper hand and had ordered these young people home. At this time an old Chinaman named Wong, non-progressionist, was the chief China Minister at Washington and Yung Wing was his assistant. The order disbanding the schools was a great blow to Yung Wing, who had spent many years in working for their establishment. This order came upon him with the suddenness of a thunder clap. He did not know which way to turn.

First, he got a petition signed by the Presidents of various American colleges setting forth the great progress that the Chinese pupils had made and offering arguments to show why the pupils should be allowed to remain to finish their education. This paper was to be conveyed to the Chinese government through the Minister at Pekin. But Yung Wing felt the need of a more powerful voice in the matter and General Grant occurred to him. He thought that if he could get General Grant’s great name added to that petition that that alone would outweigh the signatures of a thousand college professors. So the Rev. Mr. Twichell and I went down to New York to see the General. I introduced Mr. Twichell, who had come with a careful speech for the occasion in which he intended to load the General with information concerning the Chinese pupils and the Chinese question generally. But he never got the chance to deliver it. The General took the word out of his mouth and talked straight ahead and easily revealed to Twichell the fact that the General was master of the whole matter and needed no information from anybody and also the fact that he was brimful of interest in the matter. Now as always the General was not only ready to do what we asked of him but a hundred times more. He said yes, he would sign that paper if desired, but he would do better than that: he would write a personal letter to Li-Hung-Chang and do it immediately. So Twichell and I went down stairs into the lobby of the Fifth Avenue Hotel, a crowd of waiting and anxious visitors sitting in the anteroom, and in the course of half an hour he sent for us again and put into our hands his letter to Li-Hung-Chang to be sent directly and without the intervention of the American Minister or any one else. It was a clear, compact and admirably written statement of the case of the Chinese pupils with some equally clear arguments to show that the breaking up of the schools would be a mistake. We shipped the letter and prepared to wait a couple of months to see what the result would be.

But we had not to wait so long. The moment the General’s letter reached China a telegram came back from the Chinese government which was almost a copy in detail of General Grant’s letter and the cablegram ended with the peremptory command to old Minister Wong to continue the Chinese schools.

It was a marvelous exhibition of the influence of a private citizen of one country over the counsels of an empire situated on the other side of the globe. Such an influence could have been wielded by no other citizen in the world outside of that empire—in fact the policy of the Imperial government had been reversed from room 45, Fifth Avenue Hotel, New York, by a private citizen of the United States.

Gerhardt

1884. (September: at the farm at Elmira.)

Gerhardt arrived home from Paris,—leaving his wife and his little boy behind him. He had found living much more expensive at Paris than it had been in J. Q. A. Ward’s day. Consequently Ward’s estimate of $3,000 for five years had fallen woefully short. Gerhardt’s expenses for three years and a half had already amounted to $6,000. There was nothing for him to do—so he made a bust of me in the hope that it might bring him work. The times were very hard and he was not able to get anything to do.

(October.)

About this time Gerhardt heard that a competition was about ready to begin for a statue of Nathan Hale, the Revolutionary spy and patriot caught and hanged by the British. This statue had been voted by the Connecticut Legislature and the munificent price to be paid for it was $5,000. The speech which ex-Governor Hubbard had made in advocacy of the proposition was worth four times the sum.

The committee in whose hands the Legislature had placed the matter consisted of Mr. Coit, a railroad man, of New London, a modest, sensible, honorable, worthy gentleman, who while wholly unacquainted with art and confessing it, was willing and anxious to do his duty in the matter. Another committeeman was an innocent ass by the name of Barnard, who knew nothing about art and in fact about nothing else, and if he had a mind was not able to make it up on any question. As for any sense of duty, that feature was totally lacking in him—he had no notion of it whatever. The third and last committeeman was the reigning Governor of the state, Waller, a smooth-tongued liar and moral coward.

Gerhardt designed and made a clay Nathan Hale and offered it for competition.

A salaried artist of Mr. Batterson, a stone cutter, designed a figure and placed it in competition, and so also did Mr. Woods, an elderly man who was sexton of Mrs. Colt’s private church.

Woods had some talent but no genius and no instruction in art. The stone cutte

r’s man had the experience and the practice that comes from continually repeating the same forms on hideous tombstones—robust prize-fighting angels, mainly.

The figure and pedestal made by Gerhardt were worthy of a less stingy price than the Legislature had offered, decenter companionship in the competition and a cleaner and less stupid committee.

In the opinion of William C. Prime and Charles D. Warner, Gerhardt’s was a very fine work of art and these men would not have hesitated to award the contract to him. The Governor looked at the three models and said that as far as he could see Gerhardt’s was altogether the preferable design. Mr. Coit said the same. But it was found impossible to get the aged Barnard to come to look at Gerhardt’s model. He offered among other excuses that he didn’t like to give a statue to a man who still had his reputation to make—that the statue ought to be made by an artist of established reputation. When asked what artist of established reputation would make a statue for $5,000 he was not able to reply. It was difficult for some time to find out what the real reason was for this old man’s delay, but it finally came out that Mrs. Colt’s money and influence were at the bottom of it. Mrs. Colt was anxious to throw that statue into the hands of her sexton in some way or other. She wrote a letter to the Governor, in which she argued the claims of her sexton, and it presently became quite manifest that the Governor found himself in an uncomfortable position, for the reason that he had characterized the sexton’s attempt as exceedingly poor and crude, and had also stated quite distinctly that of the three models he much preferred Gerhardt’s and was ready to vote in that way.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 1.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 1. The Prince and the Pauper

The Prince and the Pauper The American Claimant

The American Claimant Eve's Diary, Complete

Eve's Diary, Complete Extracts from Adam's Diary, translated from the original ms.

Extracts from Adam's Diary, translated from the original ms. A Tramp Abroad

A Tramp Abroad The Best Short Works of Mark Twain

The Best Short Works of Mark Twain Humorous Hits and How to Hold an Audience

Humorous Hits and How to Hold an Audience The Speculative Fiction of Mark Twain

The Speculative Fiction of Mark Twain The Facts Concerning the Recent Carnival of Crime in Connecticut

The Facts Concerning the Recent Carnival of Crime in Connecticut Alonzo Fitz, and Other Stories

Alonzo Fitz, and Other Stories The $30,000 Bequest, and Other Stories

The $30,000 Bequest, and Other Stories Pudd'nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins

Pudd'nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the Undead

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the Undead Sketches New and Old

Sketches New and Old The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg

The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg A Tramp Abroad — Volume 06

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 06 A Tramp Abroad — Volume 02

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 02 The Prince and the Pauper, Part 1.

The Prince and the Pauper, Part 1. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 16 to 20

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 16 to 20 The Prince and the Pauper, Part 9.

The Prince and the Pauper, Part 9. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 21 to 25

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 21 to 25 Tom Sawyer, Detective

Tom Sawyer, Detective A Tramp Abroad (Penguin ed.)

A Tramp Abroad (Penguin ed.) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 36 to the Last

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 36 to the Last The Mysterious Stranger, and Other Stories

The Mysterious Stranger, and Other Stories A Tramp Abroad — Volume 03

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 03 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 3.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 3. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 06 to 10

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 06 to 10_preview.jpg) The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade)

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 31 to 35

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 31 to 35 The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg, and Other Stories

The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg, and Other Stories A Tramp Abroad — Volume 07

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 07 Editorial Wild Oats

Editorial Wild Oats Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 26 to 30

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 26 to 30 1601: Conversation as it was by the Social Fireside in the Time of the Tudors

1601: Conversation as it was by the Social Fireside in the Time of the Tudors A Tramp Abroad — Volume 05

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 05 Sketches New and Old, Part 1.

Sketches New and Old, Part 1. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 2.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 2. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 8.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 8. A Tramp Abroad — Volume 01

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 01 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 5.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 5. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 01 to 05

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 01 to 05 A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 1.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 1. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 4.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 4. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 2.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 2. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 7.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 7. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 3.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 3. Sketches New and Old, Part 4.

Sketches New and Old, Part 4. Sketches New and Old, Part 3.

Sketches New and Old, Part 3. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 7.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 7. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 5.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 5. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 6.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 6. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 4.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 4. Sketches New and Old, Part 2.

Sketches New and Old, Part 2. Sketches New and Old, Part 6.

Sketches New and Old, Part 6. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 11 to 15

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 11 to 15 Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc

Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc Sketches New and Old, Part 5.

Sketches New and Old, Part 5. Eve's Diary, Part 3

Eve's Diary, Part 3 Sketches New and Old, Part 7.

Sketches New and Old, Part 7. Mark Twain on Religion: What Is Man, the War Prayer, Thou Shalt Not Kill, the Fly, Letters From the Earth

Mark Twain on Religion: What Is Man, the War Prayer, Thou Shalt Not Kill, the Fly, Letters From the Earth Tales, Speeches, Essays, and Sketches

Tales, Speeches, Essays, and Sketches A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 9.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 9. Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands (version 1)

Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands (version 1) 1601

1601 Letters from the Earth

Letters from the Earth Curious Republic Of Gondour, And Other Curious Whimsical Sketches

Curious Republic Of Gondour, And Other Curious Whimsical Sketches The Mysterious Stranger

The Mysterious Stranger Life on the Mississippi

Life on the Mississippi Roughing It

Roughing It Alonzo Fitz and Other Stories

Alonzo Fitz and Other Stories The 30,000 Dollar Bequest and Other Stories

The 30,000 Dollar Bequest and Other Stories The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn taots-2

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn taots-2 A Double-Barreled Detective Story

A Double-Barreled Detective Story adam's diary.txt

adam's diary.txt A Horse's Tale

A Horse's Tale Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1

Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1 The Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins

The Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins Following the Equator

Following the Equator Goldsmith's Friend Abroad Again

Goldsmith's Friend Abroad Again No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger

No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger The Stolen White Elephant

The Stolen White Elephant The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories

The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories The Curious Republic of Gondour, and Other Whimsical Sketches

The Curious Republic of Gondour, and Other Whimsical Sketches Prince and the Pauper (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Prince and the Pauper (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Portable Mark Twain

The Portable Mark Twain Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Adventures of Tom Sawyer taots-1

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer taots-1 A Double Barrelled Detective Story

A Double Barrelled Detective Story Eve's Diary

Eve's Diary A Dog's Tale

A Dog's Tale The Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts (Literature)

The Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts (Literature) The Complete Short Stories of Mark Twain

The Complete Short Stories of Mark Twain What Is Man? and Other Essays

What Is Man? and Other Essays The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Zombie Jim

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Zombie Jim Who Is Mark Twain?

Who Is Mark Twain? Christian Science

Christian Science The Innocents Abroad

The Innocents Abroad Some Rambling Notes of an Idle Excursion

Some Rambling Notes of an Idle Excursion Autobiography of Mark Twain

Autobiography of Mark Twain Those Extraordinary Twins

Those Extraordinary Twins Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1

Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1