- Home

- Mark Twain

The Speculative Fiction of Mark Twain Page 12

The Speculative Fiction of Mark Twain Read online

Page 12

“Of course I must have drunk it, but I’m blest if I can recollect whether I did or not. Lemme see. First you poured it out, then I set down and put it before me here; next I took a sup and said it was good, and set it down and begun about old Cap’n Jimmy—and then—and then—” He was silent a moment, then said, “It’s as far as I can get. It beats me. I reckon that after that I was so kind of full of my story that I didn’t notice whether I—.” He stopped again, and there was something almost pathetic about the appealing way in which he added, “But I did drink it, didn’t I? You see me do it—didn’t you?”

I hadn’t the heart to say no.

“Why, yes, I think I did. I wasn’t noticing particularly, but it seems to me that I saw you drink it—in fact, I am about certain of it.”

I was glad I told the lie, it did him so much good, and so lightened his spirits, poor old fellow.

“Of course I done it! I’m such a fool. As a general thing I wouldn’t care, and I wouldn’t bother anything about it; but when there’s jimjams around the least little thing makes a person suspicious, you know. If you don’t mind, sir—thanks, ever so much.” He took a large sup of the new supply, praised it, set the cup down—leaning forward and fencing it around with his arms, with a labored pretense of not noticing that he was doing that—then said—

“Lemme see—where was I? Yes. Well, it happened like this. The Washingtonian Movement started up in those old times, you know, and it was Father Matthew here and Father Matthew there and Father Matthew yonder—nothing but Father Matthew and temperance all over everywheres. And temperance societies? There was millions of them, and everybody joined and took the pledge. We had one in New Bedford. Every last whaler joined—captain, crew and all. All, down to old Cap’n Jimmy. He was an old bach, his grog was his darling, he owned his ship and sailed her himself, he was independent, and he wouldn’t give in. So at last they gave it up and quit pestering him. Time rolled along, and he got awful lonesome. There wasn’t anybody to drink with, you see, and it got unbearable. So finally the day he sailed for Bering Strait he caved, and sent in his name to the society. Just as he was starting, his mate broke his leg and stopped ashore and he shipped a stranger in his place from down New York way. This fellow didn’t belong to any society, and he went aboard fixed for the voyage. Cap’n Jimmy was out three solid years; and all the whole time he had the spectacle of that mate whetting up every day and leading a life that was worth the trouble; and it nearly killed him for envy to see it. Made his mouth water, you know, in a way that was pitiful. Well, he used to get out on the peak of the bowsprit where it was private, and set there and cuss. It was his only relief from his sufferings. Mainly he cussed himself; but when he had used up all his words and couldn’t think of any new rotten things to call himself, he would turn his vocabulary over and start fresh and lay into Father Matthew and give him down the banks; and then the society; and so put in his watch as satisfactory as he could. Then he would count the days he was out, and try to reckon up about when he could hope to get home and resign from the society and start in on an all-compensating drunk that would make up for lost time. Well, when he was out three thousand years—which was his estimate, you know, though really it was only three years—he came rolling down the homestretch with every rag stretched on his poles. Middle of winter, it was, and terrible cold and stormy. He made the landfall just at sundown and had to stand watch on deck all night of course, and the rigging was caked with ice three inches thick, and the yards was bearded with icicles five foot long, and the snow laid nine inches deep on the deck and hurricanes more of it being shoveled down onto him out of the skies. And so he plowed up and down all night, cussing himself and Father Matthew and the society, and doing it better than he ever done before; and his mouth was watering so, on account of the mate whetting up right in his sight all the time, that every cuss-word come out damp, and froze solid as it fell, and in his insufferable indignation he would hit it a whack with his cane and knock it a hundred yards, and one of them took the mate in the mouth and fetched away a rank of teeth and lowered his spirits considerable. He made the dock just at early breakfast time and never waited to tie up, but jumped ashore with his jug in his hand and rushed for the society’s quarters like a deer. He met the seckatary coming out and yelled at him—

“ ‘I’ve resigned my membership!—I give you just two minutes to scrape my name off your log, d’ye hear?’

“And then the seckatary told him he’d been black-balled three years before—hadn’t ever been a member! Land, I can’t hold in, it’s coming again!”

He flung up his arms, threw his head back, spread his jaws, and made the ship quake with the thunder of his laughter, while the Superintendent of Dreams emptied the cup again and set it back in its place. When Turner came out of his fit at last he was limp and exhausted, and sat mopping his tears away and breaking at times into little feebler and feebler barks and catches of expiring laughter. Finally he fetched a deep sigh of comfort and satisfaction, and said—

“Well, it does do a person good, no mistake—on a voyage like this. I reckon—”

His eye fell on the cup. His face turned a ghastly white—

“By God she’s empty again!”

He jumped up and made a sprawling break for the door. I was frightened; I didn’t know what he might do—jump overboard, maybe. I sprang in front of him and barred the way, saying, “Come, Turner, be a man, be a man! don’t let your imagination run away with you like this”; and over his shoulder I threw a pleading look at the Superintendent of Dreams, who answered my prayer and refilled the cup from the coffee urn.

“Imagination you call it, sir! Can’t I see?—with my own eyes? Let me go—don’t stop me—I can’t stand it, I can’t stand it!”

“Turner, be reasonable—you know perfectly well your cup isn’t empty, and hasn’t been.”

That hit him. A dim light of hope and gratitude shone in his eye, and he said in a quivery voice—

“Say it again—and say it’s true. Is it true? Honor bright—you wouldn’t deceive a poor devil that’s—”

“Honor bright, man, I’m not deceiving you—look for yourself.”

Gradually he turned a timid and wary glance toward the table; then the terror went out of his face, and he said humbly—

“Well, you see I reckon I hadn’t quite got over thinking it happened the first time, and so maybe without me knowing it, that made me kind of suspicious that it would happen again, because the jimjams make you untrustful that way; and so, sure enough, I didn’t half look at the cup, and just jumped to the conclusion it had happened.” And talking so, he moved toward the sofa, hesitated a moment, and then sat down in that figure’s body again. “But I’m all right, now, and I’ll just shake these feelings off and be a man, as you say.”

The Superintendent of Dreams separated himself and moved along the sofa a foot or two away from Turner. I was glad of that; it looked like a truce. Turner swallowed his cup of coffee; I poured another; he began to sip it, the pleasant influence worked a change, and soon he was a rational man again, and comfortable. Now a sea came aboard, hit our deck-house a stunning thump, and went hissing and seething aft.

“Oh, that’s the ticket,” said Turner, “the dummdest weather that ever I went pleasure-excursioning in. And how did it get aboard?—You answer me that: there ain’t any motion to the ship. These mysteriousnesses—well, they just give me the cold shudders. And that reminds me. Do you mind my calling your attention to another peculiar thing or two?—on conditions as before—solid secrecy, you know.”

“I’ll keep it to myself. Go on.”

“The Gulf Stream’s gone to the devil!”

“What do you mean?”

“It’s the fact, I wish I may never die. From the day we sailed till now, the water’s been the same temperature right along, I’ll take my oath. The Gulf Stream don’t exist any more; she’s gone to the devil.”

“It’s incredible, Turner! You make me gasp.”

“Gasp away, if you want to; if things go on so, you ain’t going to forget how for want of practice. It’s the wooliest voyage, take it by and large—why, look here! You are a landsman, and there’s no telling what a landsman can’t overlook if he tries. For instance, have you noticed that the nights and days are exactly alike, and you can’t tell one from tother except by keeping tally?”

“Why, yes, I have noticed it in a sort of indifferent general way, but—”

“Have you kept a tally, sir?”

“No, it didn’t occur to me to do it.”

“I thought so. Now you know, you couldn’t keep it in your head, because you and your family are free to sleep as much as you like, and as it’s always dark, you sleep a good deal, and you are pretty irregular, naturally. You’ve all been a little seasick from the start—tea and toast in your own parlor here—no regular time—order it as each of you pleases. You see? You don’t go down to meals—they would keep tally for you. So you’ve lost your reckoning. I noticed it an hour ago.”

“How?”

“Well, you spoke of to-night. It ain’t to-night at all; it’s just noon, now.”

“The fact is, I don’t believe I have often thought of its being day, since we left. I’ve got into the habit of considering it night all the time; it’s the same with my wife and the children.”

“There it is, you see. Mr. Edwards, it’s perfectly awful; now ain’t it, when you come to look at it? Always night—and such dismal nights, too. It’s like being up at the pole in the winter time. And I’ll ask you to notice another thing: this sky is as empty as my sou-wester there.”

“Empty?”

“Yes, sir. I know it. You can’t get up a day, in a Christian country, that’s so solid black the sun can’t make a blurry glow of some kind in the sky at high noon—now can you?”

“No, you can’t.”

“Have you ever seen a suspicion of any such a glow in this sky?”

“Now that you mention it, I haven’t.”

He dropped his voice and said impressively—

“Because there ain’t any sun. She’s gone where the Gulf Stream twineth.”

“Turner! Don’t talk like that.”

“It’s confidential, or I wouldn’t. And the moon. She’s at the full—by the almanac she is. Why don’t she make a blur? Because there ain’t any moon. And moreover—you might rake this on-completed sky a hundred year with a drag-net and you’d never scoop a star! Why? Because there ain’t any. Now then, what is your opinion about all this?”

“Turner, it’s so gruesome and creepy that I don’t like to think about it—and I haven’t any. What is yours?”

He said, dismally—

“That the world has come to an end. Look at it yourself. Just look at the facts. Put them together and add them up, and what have you got? No Sable island; no Greenland; no Gulf Stream; no day, no proper night; weather that don’t jibe with any sample known to the Bureau; animals that would start a panic in any menagerie, chart no more use than a horse-blanket, and the heavenly bodies gone to hell! And on top of it all, that jimjam that I’ve put my hand on more than once and he warn’t there—I’ll swear it. The ship’s bewitched. You don’t believe in the jim, and I’ve sort of lost faith myself, here in the bright light; but if this cup of coffee was to—”

The cup began to glide slowly away, along the table. The hand that moved it was not visible to him. He rose slowly to his feet and stood trembling as if with an ague, his teeth knocking together and his glassy eyes staring at the cup. It slid on and on, noiseless; then it rose in the air, gradually reversed itself, poured its contents down the Superintendent’s throat—I saw the dark stream trickling its way down through his hazy breast—then it returned to the table, and without sound of contact, rested there. The mate continued to stare at it for as much as a minute; then he drew a deep breath, took up his sou-wester, and without looking to the right or the left, walked slowly out of the room like one in a trance, muttering—

“I’ve got them—I’ve had the proof.”

I said, reproachfully—

“Superintendent, why do you do that?”

“Do what?”

“Play these tricks.”

“What harm is it?”

“Harm? It could make that poor devil jump overboard.”

“No, he’s not as far gone as that.”

“For a while he was. He is a good fellow, and it was a pity to scare him so. However there are other matters that I am more concerned about just now.

“Can I help?”

“Why yes, you can; and I don’t know any one else that can.”

“Very well, go on.”

“By the dead-reckoning we have come twenty-three hundred miles.”

“The actual distance is twenty-three-fifty.”

“Straight as a dart in the one direction—mainly.”

“Apparently.”

“Why do you say apparently? Haven’t we come straight?”

“Go on with the rest. What were you going to say?”

“This. Doesn’t it strike you that this is a pretty large drop of water?”

“No. It is about the usual size—six thousand miles across.”

“Six thousand miles!”

“Yes.”

“Twice as far as from New York to Liverpool?”

“Yes.”

“I must say it is more of a voyage than I counted on. And we are not a great deal more than halfway across, yet. When shall we get in?”

“It will be some time yet.”

“That is not very definite. Two weeks?”

“More than that.”

I was getting a little uneasy.

“But how much more? A week?”

“All of that. More, perhaps.”

“Why don’t you tell me? A month more, do you think?”

“I am afraid so. Possibly two—possibly longer, even.”

I was getting seriously disturbed by now.

“Why, we are sure to run out of provisions and water.”

“No you’ll not. I’ve looked out for that. It is what you are loaded with.”

“Is that so? How does that come?”

“Because the ship is chartered for a voyage of discovery. Ostensibly she goes to England, takes aboard some scientists, then sails for the South pole.”

“I see. You are deep.”

“I understand my business.”

I turned the matter over in my mind a moment, then said—

“It is more of a voyage than I was expecting, but I am not of a worrying disposition, so I do not care, so long as we are not going to suffer hunger and thirst.”

“Make yourself easy, as to that. Let the trip last as long as it may, you will not run short of food and water, I go bail for that.”

“All right, then. Now explain this riddle to me. Why is it always night?”

“That is easy. All of the drop of water is outside the luminous circle of the microscope except one thin and delicate rim of it. We are in the shadow; consequently in the dark.”

“In the shadow of what?”

“Of the brazen end of the lens-holder.”

“How can it cover such a spread with its shadow?”

“Because it is several thousand miles in diameter. For dimensions, that is nothing. The glass slide which it is pressing against, and which forms the bottom of the ocean we are sailing upon, is thirty thousand miles long, and the length of the microscope barrel is a hundred and twenty thousand. Now then, if—”

“You make me dizzy. I—”

“If you should thrust that glass slide through what you call the ‘great’ globe, eleven thousand miles of it would stand out on each side—it would be like impaling an orange on a table-knife. And so—”

“It gives me the head-ache. Are these the fictitious proportions which we and our surroundings and belongings have acquired by being reduced to microscopic objects?”

“They are the proportions, yes—but they are no

t fictitious. You do not notice that you yourself are in any way diminished in size, do you?”

“No, I am my usual size, so far as I can see.”

“The same with the men, the ship and everything?”

“Yes—all natural.”

“Very good; nothing but the laws and conditions have undergone a change. You came from a small and very insignificant world. The one you are in now is proportioned according to microscopic standards—that is to say, it is inconceivably stupendous and imposing.”

It was food for thought. There was something overpowering in the situation, something sublime. It took me a while to shake off the spell and drag myself back to speech. Presently I said—

“I am content; I do not regret the voyage—far from it. I would not change places with any man in that cramped little world. But tell me—is it always going to be dark?”

“Not if you ever come into the luminous circle under the lens. Indeed you will not find that dark!”

“If we ever. What do you mean by that? We are making steady good time; we are cutting across this sea on a straight course.”

“Apparently.”

“There is no apparently about it.”

“You might be going around in a small and not rapidly widening circle.”

“Nothing of the kind. Look at the tell-tale compass over your head.”

“I see it.”

“We changed to this easterly course to satisfy—well, to satisfy everybody but me. It is a pretense of aiming for England—in a drop of water! Have you noticed that needle before?”

“Yes, a number of times.”

“To-day, for instance?”

“Yes—often.”

“Has it varied a jot?”

“Not a jot.”

“Hasn’t it always kept the place appointed for it—from the start?”

“Yes, always.”

“Very well. First we sailed a northerly course; then tilted easterly; and now it is more so. How is that going around in a circle?”

He was silent. I put it at him again. He answered with lazy indifference—

“I merely threw out the suggestion.”

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 1.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 1. The Prince and the Pauper

The Prince and the Pauper The American Claimant

The American Claimant Eve's Diary, Complete

Eve's Diary, Complete Extracts from Adam's Diary, translated from the original ms.

Extracts from Adam's Diary, translated from the original ms. A Tramp Abroad

A Tramp Abroad The Best Short Works of Mark Twain

The Best Short Works of Mark Twain Humorous Hits and How to Hold an Audience

Humorous Hits and How to Hold an Audience The Speculative Fiction of Mark Twain

The Speculative Fiction of Mark Twain The Facts Concerning the Recent Carnival of Crime in Connecticut

The Facts Concerning the Recent Carnival of Crime in Connecticut Alonzo Fitz, and Other Stories

Alonzo Fitz, and Other Stories The $30,000 Bequest, and Other Stories

The $30,000 Bequest, and Other Stories Pudd'nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins

Pudd'nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the Undead

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the Undead Sketches New and Old

Sketches New and Old The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg

The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg A Tramp Abroad — Volume 06

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 06 A Tramp Abroad — Volume 02

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 02 The Prince and the Pauper, Part 1.

The Prince and the Pauper, Part 1. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 16 to 20

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 16 to 20 The Prince and the Pauper, Part 9.

The Prince and the Pauper, Part 9. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 21 to 25

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 21 to 25 Tom Sawyer, Detective

Tom Sawyer, Detective A Tramp Abroad (Penguin ed.)

A Tramp Abroad (Penguin ed.) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 36 to the Last

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 36 to the Last The Mysterious Stranger, and Other Stories

The Mysterious Stranger, and Other Stories A Tramp Abroad — Volume 03

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 03 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 3.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 3. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 06 to 10

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 06 to 10_preview.jpg) The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade)

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 31 to 35

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 31 to 35 The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg, and Other Stories

The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg, and Other Stories A Tramp Abroad — Volume 07

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 07 Editorial Wild Oats

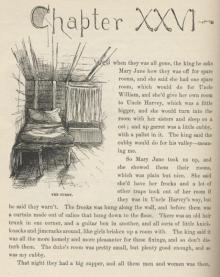

Editorial Wild Oats Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 26 to 30

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 26 to 30 1601: Conversation as it was by the Social Fireside in the Time of the Tudors

1601: Conversation as it was by the Social Fireside in the Time of the Tudors A Tramp Abroad — Volume 05

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 05 Sketches New and Old, Part 1.

Sketches New and Old, Part 1. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 2.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 2. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 8.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 8. A Tramp Abroad — Volume 01

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 01 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 5.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 5. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 01 to 05

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 01 to 05 A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 1.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 1. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 4.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 4. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 2.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 2. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 7.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 7. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 3.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 3. Sketches New and Old, Part 4.

Sketches New and Old, Part 4. Sketches New and Old, Part 3.

Sketches New and Old, Part 3. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 7.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 7. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 5.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 5. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 6.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 6. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 4.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 4. Sketches New and Old, Part 2.

Sketches New and Old, Part 2. Sketches New and Old, Part 6.

Sketches New and Old, Part 6. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 11 to 15

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 11 to 15 Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc

Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc Sketches New and Old, Part 5.

Sketches New and Old, Part 5. Eve's Diary, Part 3

Eve's Diary, Part 3 Sketches New and Old, Part 7.

Sketches New and Old, Part 7. Mark Twain on Religion: What Is Man, the War Prayer, Thou Shalt Not Kill, the Fly, Letters From the Earth

Mark Twain on Religion: What Is Man, the War Prayer, Thou Shalt Not Kill, the Fly, Letters From the Earth Tales, Speeches, Essays, and Sketches

Tales, Speeches, Essays, and Sketches A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 9.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 9. Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands (version 1)

Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands (version 1) 1601

1601 Letters from the Earth

Letters from the Earth Curious Republic Of Gondour, And Other Curious Whimsical Sketches

Curious Republic Of Gondour, And Other Curious Whimsical Sketches The Mysterious Stranger

The Mysterious Stranger Life on the Mississippi

Life on the Mississippi Roughing It

Roughing It Alonzo Fitz and Other Stories

Alonzo Fitz and Other Stories The 30,000 Dollar Bequest and Other Stories

The 30,000 Dollar Bequest and Other Stories The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn taots-2

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn taots-2 A Double-Barreled Detective Story

A Double-Barreled Detective Story adam's diary.txt

adam's diary.txt A Horse's Tale

A Horse's Tale Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1

Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1 The Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins

The Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins Following the Equator

Following the Equator Goldsmith's Friend Abroad Again

Goldsmith's Friend Abroad Again No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger

No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger The Stolen White Elephant

The Stolen White Elephant The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories

The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories The Curious Republic of Gondour, and Other Whimsical Sketches

The Curious Republic of Gondour, and Other Whimsical Sketches Prince and the Pauper (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Prince and the Pauper (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Portable Mark Twain

The Portable Mark Twain Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Adventures of Tom Sawyer taots-1

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer taots-1 A Double Barrelled Detective Story

A Double Barrelled Detective Story Eve's Diary

Eve's Diary A Dog's Tale

A Dog's Tale The Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts (Literature)

The Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts (Literature) The Complete Short Stories of Mark Twain

The Complete Short Stories of Mark Twain What Is Man? and Other Essays

What Is Man? and Other Essays The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Zombie Jim

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Zombie Jim Who Is Mark Twain?

Who Is Mark Twain? Christian Science

Christian Science The Innocents Abroad

The Innocents Abroad Some Rambling Notes of an Idle Excursion

Some Rambling Notes of an Idle Excursion Autobiography of Mark Twain

Autobiography of Mark Twain Those Extraordinary Twins

Those Extraordinary Twins Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1

Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1