- Home

- Mark Twain

No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger Page 2

No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger Read online

Page 2

Yes, he put it in the bond, and the prior said he didn’t want the bridge built yet, but would soon appoint a day—perhaps in about a week. There was an old monk wavering along between life and death, and the prior told the watchers to keep a sharp eye out and let him know as soon as they saw that the monk was actually dying. Towards midnight the 9th of December the watchers brought him word, and he summoned the Devil and the bridge was begun. All the rest of the night the prior and the Brotherhood sat up and prayed that the dying one might be given strength to rise up and walk across the bridge at dawn—strength enough, but not too much. The prayer was heard, and it made great excitement in heaven; insomuch that all the heavenly host got up before dawn and came down to see; and there they were, clouds and clouds of angels filling all the air above the bridge; and the dying monk tottered across, and just had strength to get over; then he fell dead just as the Devil was reaching for him, and as his soul escaped the angels swooped down and caught it and flew up to heaven with it, laughing and jeering, and Satan found he hadn’t anything but a useless carcase.

He was very angry, and charged the prior with cheating him, and said “this isn’t a Christian,” but the prior said “Yes it is, it’s a dead one.” Then the prior and all the monks went through with a great lot of mock ceremonies, pretending it was to assuage the Devil and reconcile him, but really it was only to make fun of him and stir up his bile more than ever. So at last he gave them all a solid good cursing, they laughing at him all the time. Then he raised a black storm of thunder and lightning and wind and flew away in it; and as he went the spike on the end of his tail caught on a capstone and tore it away; and there it always lay, throughout the centuries, as proof of what he had done. I have seen it myself, a thousand times. Such things speak louder than written records; for written records can lie, unless they are set down by a priest. The mock Assuaging is repeated every 9th of December, to this day, in memory of that holy thought of the prior’s which rescued an imperiled Christian soul from the odious Enemy of mankind.

There have been better priests, in some ways, than Father Adolf, for he had his failings, but there was never one in our commune who was held in more solemn and awful respect. This was because he had absolutely no fear of the Devil. He was the only Christian I have ever known of whom that could be truly said. People stood in deep dread of him, on that account; for they thought there must be something supernatural about him, else he could not be so bold and so confident. All men speak in bitter disapproval of the Devil, but they do it reverently, not flippantly; but Father Adolf’s way was very different; he called him by every vile and putrid name he could lay his tongue to, and it made every one shudder that heard him; and often he would even speak of him scornfully and scoffingly; then the people crossed themselves and went quickly out of his presence, fearing that something fearful might happen; and this was natural, for after all is said and done Satan is a sacred character, being mentioned in the Bible, and it cannot be proper to utter lightly the sacred names, lest heaven itself should resent it.

Father Adolf had actually met Satan face to face, more than once, and defied him. This was known to be so. Father Adolf said it himself. He never made any secret of it, but spoke it right out. And that he was speaking true, there was proof, in at least one instance; for on that occasion he quarreled with the Enemy, and intrepidly threw his bottle at him, and there, upon the wall of his study was the ruddy splotch where it struck and broke.

The priest that we all loved best and were sorriest for, was Father Peter. But the Bishop suspended him for talking around in conversation that God was all goodness and would find a way to save all his poor human children. It was a horrible thing to say, but there was never any absolute proof that Father Peter said it; and it was out of character for him to say it, too, for he was always good and gentle and truthful, and a good Catholic, and always teaching in the pulpit just what the Church required, and nothing else. But there it was, you see: he wasn’t charged with saying it in the pulpit, where all the congregation could hear and testify, but only outside, in talk; and it is easy for enemies to manufacture that. Father Peter denied it; but no matter, Father Adolf wanted his place, and he told the Bishop, and swore to it, that he overheard Father Peter say it; heard Father Peter say it to his niece, when Father Adolf was behind the door listening—for he was suspicious of Father Peter’s soundness, he said, and the interests of religion required that he be watched.

The niece, Gretchen, denied it, and implored the Bishop to believe her and spare her old uncle from poverty and disgrace; but Father Adolf had been poisoning the Bishop against the old man a long time privately, and he wouldn’t listen; for he had a deep admiration of Father Adolf’s bravery toward the Devil, and an awe of him on account of his having met the Devil face to face; and so he was a slave to Father Adolf’s influence. He suspended Father Peter, indefinitely, though he wouldn’t go so far as to excommunicate him on the evidence of only one witness; and now Father Peter had been out a couple of years, and Father Adolf had his flock.

Those had been hard years for the old priest and Gretchen. They had been favorites, but of course that changed when they came under the shadow of the Bishop’s frown. Many of their friends fell away entirely, and the rest became cool and distant. Gretchen was a lovely girl of eighteen, when the trouble came, and she had the best head in the village, and the most in it. She taught the harp, and earned all her clothes and pocket money by her own industry. But her scholars fell off one by one, now; she was forgotten when there were dances and parties among the youth of the village; the young fellows stopped coming to the house, all except Wilhelm Meidling—and he could have been spared; she and her uncle were sad and forlorn in their neglect and disgrace, and the sunshine was gone out of their lives. Matters went worse and worse, all through the two years. Clothes were wearing out, bread was harder and harder to get. And now at last, the very end was come. Solomon Isaacs had lent all the money he was willing to put on the house, and gave notice that tomorrow he should foreclose.

Chapter 2

I had been familiar with that village life, but now for as much as a year I had been out of it, and was busy learning a trade. I was more curiously than pleasantly situated. I have spoken of Castle Rosenfeld; I have also mentioned a precipice which overlooked the river. Well, along this precipice stretched the towered and battlemented mass of a similar castle—prodigious, vine-clad, stately and beautiful, but mouldering to ruin. The great line that had possessed it and made it their chief home during four or five centuries was extinct, and no scion of it had lived in it now for a hundred years. It was a stanch old pile, and the greater part of it was still habitable. Inside, the ravages of time and neglect were less evident than they were outside. As a rule the spacious chambers and the vast corridors, ballrooms, banqueting halls and rooms of state were bare and melancholy and cobwebbed, it is true, but the walls and floors were in tolerable condition, and they could have been lived in. In some of the rooms the decayed and ancient furniture still remained, but if the empty ones were pathetic to the view, these were sadder still.

This old castle was not wholly destitute of life. By grace of the Prince over the river, who owned it, my master, with his little household, had for many years been occupying a small portion of it, near the centre of the mass. The castle could have housed a thousand persons; consequently, as you may say, this handful was lost in it, like a swallow’s nest in a cliff.

My master was a printer. His was a new art, being only thirty or forty years old, and almost unknown in Austria. Very few persons in our secluded region had ever seen a printed page, few had any very clear idea about the art of printing, and perhaps still fewer had any curiosity concerning it or felt any interest in it. Yet we had to conduct our business with some degree of privacy, on account of the Church. The Church was opposed to the cheapening of books and the indiscriminate dissemination of knowledge. Our villagers did not trouble themselves about our work, and had no commerce in it; we published nothing

there, and printed nothing that they could have read, they being ignorant of abstruse sciences and the dead languages.

We were a mixed family. My master, Heinrich Stein, was portly, and of a grave and dignified carriage, with a large and benevolent face and calm deep eyes—a patient man whose temper could stand much before it broke. His head was bald, with a valance of silky white hair hanging around it, his face was clean shaven, his raiment was good and fine, but not rich. He was a scholar, and a dreamer or a thinker, and loved learning and study, and would have submerged his mind all the days and nights in his books and been pleasantly and peacefully unconscious of his surroundings, if God had been willing. His complexion was younger than his hair; he was four or five years short of sixty.

A large part of his surroundings consisted of his wife. She was well along in life, and was long and lean and flat-breasted, and had an active and vicious tongue and a diligent and devilish spirit, and more religion than was good for her, considering the quality of it. She hungered for money, and believed there was a treasure hid in the black deeps of the castle somewhere; and between fretting and sweating about that and trying to bring sinners nearer to God when any fell in her way she was able to fill up her time and save her life from getting uninteresting and her soul from getting mouldy. There was old tradition for the treasure, and the word of Balthasar Hoffman thereto. He had come from a long way off, and had brought a great reputation with him, which he concealed in our family the best he could, for he had no more ambition to be burnt by the Church than another. He lived with us on light salary and board, and worked the constellations for the treasure. He had an easy berth and was not likely to lose his job if the constellations held out, for it was Frau Stein that hired him; and her faith in him, as in all things she had at heart, was of the staying kind. Inside the walls, where was safety, he clothed himself as Egyptians and magicians should, and moved stately, robed in black velvet starred and mooned and cometed and sun’d with the symbols of his trade done in silver, and on his head a conical tower with like symbols glinting from it. When he at intervals went outside he left his business suit behind, with good discretion, and went dressed like anybody else and looking the Christian with such cunning art that St. Peter would have let him in quite as a matter of course, and probably asked him to take something. Very naturally we were all afraid of him—abjectly so, I suppose I may say—though Ernest Wasserman professed that he wasn’t. Not that he did it publicly; no, he didn’t; for, with all his talk, Ernest Wasserman had a judgment in choosing the right place for it that never forsook him. He wasn’t even afraid of ghosts, if you let him tell it; and not only that but didn’t believe in them. That is to say, he said he didn’t believe in them. The truth is, he would say any foolish thing that he thought would make him conspicuous.

To return to Frau Stein. This masterly devil was the master’s second wife, and before that she had been the widow Vogel. She had brought into the family a young thing by her first marriage, and this girl was now seventeen and a blister, so to speak; for she was a second edition of her mother—just plain galley-proof, neither revised nor corrected, full of turned letters, wrong fonts, outs and doubles, as we say in the printing-shop—in a word, pi, if you want to put it remorselessly strong and yet not strain the facts. Yet if it ever would be fair to strain facts it would be fair in her case, for she was not loath to strain them herself when so minded. Moses Haas said that whenever she took up an en-quad fact, just watch her and you would see her try to cram it in where there wasn’t breathing-room for a 4-m space; and she’d do it, too, if she had to take the sheep-foot to it. Isn’t it neat! Doesn’t it describe it to a dot? Well, he could say such things, Moses could—as malicious a devil as we had on the place, but as bright as a lightning-bug and as sudden, when he was in the humor. He had a talent for getting himself hated, and always had it out at usury. That daughter kept the name she was born to—Maria Vogel; it was her mother’s preference and her own. Both were proud of it, without any reason, except reasons which they invented, themselves, from time to time, as a market offered. Some of the Vogels may have been distinguished, by not getting hanged, Moses thought, but no one attached much importance to what the mother and daughter claimed for them. Maria had plenty of energy and vivacity and tongue, and was shapely enough but not pretty, barring her eyes, which had all kinds of fire in them, according to the mood of the moment—opal-fire, fox-fire, hell-fire, and the rest. She hadn’t any fear, broadly speaking. Perhaps she had none at all, except for Satan, and ghosts, and witches and the priest and the magician, and a sort of fear of God in the dark, and of the lightning when she had been blaspheming and hadn’t time to get in aves enough to square up and cash-in. She despised Marget Regen, the master’s niece, along with Marget’s mother, Frau Regen, who was the master’s sister and a dependent and bedridden widow. She loved Gustav Fischer, the big and blonde and handsome and good-hearted journeyman, and detested the rest of the tribe impartially, I think. Gustav did not reciprocate.

Marget Regen was Maria’s age—seventeen. She was lithe and graceful and trim-built as a fish, and she was a blue-eyed blonde, and soft and sweet and innocent and shrinking and winning and gentle and beautiful; just a vision for the eyes, worshipful, adorable, enchanting; but that wasn’t the hive for her. She was a kitten in a menagerie.

She was a second edition of what her mother had been at her age; but struck from the standing forms and needing no revising, as one says in the printing-shop. That poor meek mother! yonder she had lain, partially paralysed, ever since her brother my master had brought her eagerly there a dear and lovely young widow with her little child fifteen years before; the pair had been welcome, and had forgotten their poverty and poor-relation estate and been happy during three whole years. Then came the new wife with her five-year brat, and a change began. The new wife was never able to root out the master’s love for his sister, nor to drive sister and child from under the roof, but she accomplished the rest: as soon as she had gotten her lord properly trained to harness, she shortened his visits to his sister and made them infrequent. But she made up for this by going frequently herself and roasting the widow, as the saying is.

Next was old Katrina. She was cook and housekeeper; her forbears had served the master’s people and none else for three or four generations; she was sixty, and had served the master all his life, from the time when she was a little girl and he was a swaddled baby. She was erect, straight, six feet high, with the port and stride of a soldier; she was independent and masterful, and her fears were limited to the supernatural. She believed she could whip anybody on the place, and would have considered an invitation a favor. As far as her allegiance stretched, she paid it with affection and reverence, but it did not extend beyond “her family”—the master, his sister, and Marget. She regarded Frau Vogel and Maria as aliens and intruders, and was frank about saying so.

She had under her two strapping young wenches—Sara and Duffles (a nickname), and a manservant, Jacob, and a porter, Fritz.

Next, we have the printing force.

Adam Binks, sixty years old, learnèd bachelor, proof-reader, poor, disappointed, surly.

Hans Katzenyammer, 36, printer, huge, strong, freckled, redheaded, rough. When drunk, quarrelsome. Drunk when opportunity offered.

Moses Haas, 28, printer; a looker-out for himself; liable to say acid things about people and to people; take him all around, not a pleasant character.

Barty Langbein, 15; cripple; general-utility lad; sunny spirit; affectionate; could play the fiddle.

Ernest Wasserman, 17, apprentice; braggart, malicious, hateful, coward, liar, cruel, underhanded, treacherous. He and Moses had a sort of half fondness for each other, which was natural, they having one or more traits in common, down among the lower grades of traits.

Gustav Fischer, 27, printer; large, well built, shapely and muscular; quiet, brave, kindly, a good disposition, just and fair; a slow temper to ignite, but a reliable burner when well going. He was about as much out of

place as was Marget. He was the best man of them all, and deserved to be in better company.

Last of all comes August Feldner, 16, ’prentice. This is myself.

Chapter 3

Of several conveniences there was no lack; among them, fire-wood and room. There was no end of room, we had it to waste. Big or little chambers for all—suit yourself, and change when you liked. For a kitchen we used a spacious room which was high up over the massive and frowning gateway of the castle and looked down the woody steeps and southward over the receding plain.

It opened into a great room with the same outlook, and this we used as dining room, drinking room, quarreling room—in a word, family room. Above its vast fire-place, which was flanked with fluted columns, rose the wide granite mantel, heavily carved, to the high ceiling. With a cart-load of logs blazing here within and a snow-tempest howling and whirling outside, it was a heaven of a place for comfort and contentment and cosiness, and the exchange of injurious personalities. Especially after supper, with the lamps going and the day’s work done. It was not the tribe’s custom to hurry to bed.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 1.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 1. The Prince and the Pauper

The Prince and the Pauper The American Claimant

The American Claimant Eve's Diary, Complete

Eve's Diary, Complete Extracts from Adam's Diary, translated from the original ms.

Extracts from Adam's Diary, translated from the original ms. A Tramp Abroad

A Tramp Abroad The Best Short Works of Mark Twain

The Best Short Works of Mark Twain Humorous Hits and How to Hold an Audience

Humorous Hits and How to Hold an Audience The Speculative Fiction of Mark Twain

The Speculative Fiction of Mark Twain The Facts Concerning the Recent Carnival of Crime in Connecticut

The Facts Concerning the Recent Carnival of Crime in Connecticut Alonzo Fitz, and Other Stories

Alonzo Fitz, and Other Stories The $30,000 Bequest, and Other Stories

The $30,000 Bequest, and Other Stories Pudd'nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins

Pudd'nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the Undead

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the Undead Sketches New and Old

Sketches New and Old The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg

The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg A Tramp Abroad — Volume 06

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 06 A Tramp Abroad — Volume 02

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 02 The Prince and the Pauper, Part 1.

The Prince and the Pauper, Part 1. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 16 to 20

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 16 to 20 The Prince and the Pauper, Part 9.

The Prince and the Pauper, Part 9. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 21 to 25

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 21 to 25 Tom Sawyer, Detective

Tom Sawyer, Detective A Tramp Abroad (Penguin ed.)

A Tramp Abroad (Penguin ed.) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 36 to the Last

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 36 to the Last The Mysterious Stranger, and Other Stories

The Mysterious Stranger, and Other Stories A Tramp Abroad — Volume 03

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 03 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 3.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 3. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 06 to 10

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 06 to 10_preview.jpg) The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade)

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 31 to 35

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 31 to 35 The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg, and Other Stories

The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg, and Other Stories A Tramp Abroad — Volume 07

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 07 Editorial Wild Oats

Editorial Wild Oats Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 26 to 30

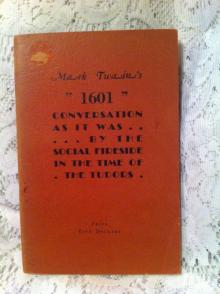

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 26 to 30 1601: Conversation as it was by the Social Fireside in the Time of the Tudors

1601: Conversation as it was by the Social Fireside in the Time of the Tudors A Tramp Abroad — Volume 05

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 05 Sketches New and Old, Part 1.

Sketches New and Old, Part 1. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 2.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 2. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 8.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 8. A Tramp Abroad — Volume 01

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 01 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 5.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 5. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 01 to 05

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 01 to 05 A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 1.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 1. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 4.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 4. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 2.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 2. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 7.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 7. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 3.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 3. Sketches New and Old, Part 4.

Sketches New and Old, Part 4. Sketches New and Old, Part 3.

Sketches New and Old, Part 3. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 7.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 7. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 5.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 5. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 6.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 6. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 4.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 4. Sketches New and Old, Part 2.

Sketches New and Old, Part 2. Sketches New and Old, Part 6.

Sketches New and Old, Part 6. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 11 to 15

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 11 to 15 Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc

Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc Sketches New and Old, Part 5.

Sketches New and Old, Part 5. Eve's Diary, Part 3

Eve's Diary, Part 3 Sketches New and Old, Part 7.

Sketches New and Old, Part 7. Mark Twain on Religion: What Is Man, the War Prayer, Thou Shalt Not Kill, the Fly, Letters From the Earth

Mark Twain on Religion: What Is Man, the War Prayer, Thou Shalt Not Kill, the Fly, Letters From the Earth Tales, Speeches, Essays, and Sketches

Tales, Speeches, Essays, and Sketches A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 9.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 9. Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands (version 1)

Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands (version 1) 1601

1601 Letters from the Earth

Letters from the Earth Curious Republic Of Gondour, And Other Curious Whimsical Sketches

Curious Republic Of Gondour, And Other Curious Whimsical Sketches The Mysterious Stranger

The Mysterious Stranger Life on the Mississippi

Life on the Mississippi Roughing It

Roughing It Alonzo Fitz and Other Stories

Alonzo Fitz and Other Stories The 30,000 Dollar Bequest and Other Stories

The 30,000 Dollar Bequest and Other Stories The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn taots-2

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn taots-2 A Double-Barreled Detective Story

A Double-Barreled Detective Story adam's diary.txt

adam's diary.txt A Horse's Tale

A Horse's Tale Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1

Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1 The Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins

The Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins Following the Equator

Following the Equator Goldsmith's Friend Abroad Again

Goldsmith's Friend Abroad Again No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger

No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger The Stolen White Elephant

The Stolen White Elephant The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories

The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories The Curious Republic of Gondour, and Other Whimsical Sketches

The Curious Republic of Gondour, and Other Whimsical Sketches Prince and the Pauper (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Prince and the Pauper (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Portable Mark Twain

The Portable Mark Twain Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Adventures of Tom Sawyer taots-1

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer taots-1 A Double Barrelled Detective Story

A Double Barrelled Detective Story Eve's Diary

Eve's Diary A Dog's Tale

A Dog's Tale The Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts (Literature)

The Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts (Literature) The Complete Short Stories of Mark Twain

The Complete Short Stories of Mark Twain What Is Man? and Other Essays

What Is Man? and Other Essays The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Zombie Jim

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Zombie Jim Who Is Mark Twain?

Who Is Mark Twain? Christian Science

Christian Science The Innocents Abroad

The Innocents Abroad Some Rambling Notes of an Idle Excursion

Some Rambling Notes of an Idle Excursion Autobiography of Mark Twain

Autobiography of Mark Twain Those Extraordinary Twins

Those Extraordinary Twins Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1

Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1