- Home

- Mark Twain

Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1 Page 25

Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1 Read online

Page 25

A figure sped across the stage, touched the lecturer on the shoulder, then bent forward toward the audience, made a trumpet of its hands and shouted—

This manuscript, like the previous two, belongs to the series of biographies Clemens was writing in 1898–99 instead of continuing to work in the more traditional format for an autobiography. It is obviously related in other ways to Clemens’s reminiscences in “Lecture-Times,” but it starts somewhat earlier, when he was a newspaper reporter in San Francisco, and extends to his 1871–72 lecture tour, during which he relied on Ralph Keeler for companionship in “lecture-flights” made out to the suburbs around Boston. Paine printed this text with his usual errors and omissions (MTA, 1:154–64). Neider reprinted only part of it, inserting excerpts from “Lecture-Times” and the Autobiographical Dictations of 11 and 12 October 1906 (AMT 161–66).

Ralph Keeler

He was a Californian. I probably knew him in San Francisco in the early days—about 1865—when I was a newspaper reporter and Bret Harte, Ambrose Bierce, Charles Warren Stoddard and Prentice Mulford were doing young literary work for Mr. Joe Lawrence’s weekly periodical The Golden Era. At any rate I knew him in Boston a few years later, where he comraded with Howells, Aldrich, Boyle O’Reilly, and James T. Fields, and was greatly liked by them. I say he comraded with them, and that is the proper term, though he would not have given the relationship so familiar a name himself, for he was the modestest young fellow that ever was, and looked humbly up to those distinguished men from his lowly obscurity and was boyishly grateful for the friendly notice they took of him, and frankly grateful for it; and when he got a smile and a nod from Mr. Emerson and Mr. Whittier and Holmes and Lowell and Longfellow, his happiness was the prettiest thing in the world to see. He was not more than twenty-four at this time; the native sweetness of his disposition had not been marred by cares and disappointments; he was buoyant and hopeful, simple-hearted, and full of the most engaging and unexacting little literary ambitions, and whomsoever he met became his friend and—by some natural and unexplained impulse—took him under protection.

He probably never had a home nor a boyhood. He had wandered to California as a little chap from somewhere or other, and had cheerfully achieved his bread in various humble callings, educating himself as he went along, and having a good and satisfactory time. Among his various industries was clog-dancing in a “nigger” show. When he was about twenty years old he scraped together $85—in greenbacks, worth about half that sum in gold—and on this capital he made the tour of Europe and published an account of his travels in the Atlantic Monthly. When he was about twenty-two he wrote a novel called “Gloverson and His Silent Partners;” and not only that, but found a publisher for it. But that was not really a surprising thing, in his case, for not even a publisher is hard-hearted enough to be able to say no to some people—and Ralph was one of those people. His gratitude for a favor granted him was so simple and sincere and so eloquent and touching that a publisher would recognize that if there was no money in the book there was still a profit to be had out of it beyond the value of money and above money’s reach. There was no money in that book; not a single penny; but Ralph Keeler always spoke of his publisher as other people speak of divinities. The publisher lost $200 or $300 on the book, of course, and knew he would lose it when he made the venture, but he got much more than the worth of it back in the author’s adoring admiration of him.

Ralph had little or nothing to do, and he often went out with me to the small lecture-towns in the neighborhood of Boston. These lay within an hour of town, and we usually started at six or thereabouts, and returned to the city in the morning. It took about a month to do these Boston annexes, and that was the easiest and pleasantest month of the four or five which constituted the “lecture season.” The “lyceum system” was in full flower in those days, and James Redpath’s Bureau in School street, Boston, had the management of it throughout the Northern States and Canada. Redpath farmed out the lecturers in groups of six or eight to the lyceums all over the country at an average of about $100 a night for each lecturer. His commission was ten per cent; each lecturer appeared about one hundred and ten nights in the season. There were a number of good drawing names in his list: Henry Ward Beecher; Anna Dickinson; John B. Gough; Horace Greeley; Wendell Phillips; Petroleum V. Nasby; Josh Billings; Hayes, the Arctic explorer; Vincent; the English astronomer; Parsons, Irish orator; Agassiz. He had in his list twenty or thirty men and women of light consequence and limited reputation who wrought for fees ranging from $25 to $50. Their names have perished long ago. Nothing but art could find them a chance on the platform. Redpath furnished that art. All the lyceums wanted the big guns, and wanted them yearningly, longingly, strenuously. Redpath granted their prayers—on this condition: for each house-filler allotted them they must hire several of his house-emptiers. This arrangement permitted the lyceums to get through alive for a few years, but in the end it killed them all and abolished the lecture business.

Beecher, Gough, Nasby and Anna Dickinson were the only lecturers who knew their own value and exacted it. In towns their fee was $200 and $250; in cities $400. The lyceum always got a profit out of these four (weather permitting), but generally lost it again on the house-emptiers.

There were two women who should have been house-emptiers—Olive Logan and Kate Field—but during a season or two they were not. They charged $100, and were recognized house-fillers for certainly two years. After that they were capable emptiers and were presently shelved. Kate Field had made a wide spasmodic notoriety in 1867 by some letters which she sent from Boston—by telegraph—to the Tribune about Dickens’s readings there in the beginning of his triumphant American tour. The letters were a frenzy of praise—praise which approached idolatry—and this was the right and welcome key to strike, for the country was itself in a frenzy of enthusiasm about Dickens. Then the idea of telegraphing a newspaper letter was new and astonishing, and the wonder of it was in everyone’s mouth. Kate Field became a celebrity at once. By and by she went on the platform; but two or three years had elapsed and her subject—Dickens—had now lost its freshness and its interest. For a while people went to see her, because of her name; but her lecture was poor and her delivery repellently artificial; consequently when the country’s desire to look at her had been appeased, the platform forsook her.

She was a good creature, and the acquisition of a perishable and fleeting notoriety was the disaster of her life. To her it was infinitely precious, and she tried hard, in various ways, during more than a quarter of a century, to keep a semblance of life in it, but her efforts were but moderately successful. She died in the Sandwich Islands, regretted by her friends and forgotten of the world.

Olive Logan’s notoriety grew out of—only the initiated knew what. Apparently it was a manufactured notoriety, not an earned one. She did write and publish little things in newspapers and obscure periodicals, but there was no talent in them, and nothing resembling it. In a century they would not have made her known. Her name was really built up out of newspaper paragraphs set afloat by her husband, who was a small-salaried minor journalist. During a year or two this kind of paragraphing was persistent; one could seldom pick up a newspaper without encountering it.

“It is said that Olive Logan has taken a cottage at Nahant, and will spend the summer there.”

“Olive Logan has set her face decidedly against the adoption of the short skirt for afternoon wear.”

“The report that Olive Logan will spend the coming winter in Paris is premature. She has not yet made up her mind.”

“Olive Logan was present at Wallack’s on Saturday evening, and was outspoken in her approval of the new piece.”

“Olive Logan has so far recovered from her alarming illness that if she continues to improve her physicians will cease from issuing bulletins tomorrow.”

The result of this daily advertising was very curious. Olive Logan’s name was as familiar to a simple public as was that of any celebrity of the tim

e, and people talked with interest about her doings and movements, and gravely discussed her opinions. Now and then an ignorant person from the backwoods would proceed to inform himself, and then there were surprises in store for all concerned:

“Who is Olive Logan?”

The listeners were astonished to find that they couldn’t answer the question. It had never occurred to them to inquire into the matter.

“What has she done?”

The listeners were dumb again. They didn’t know. They hadn’t inquired.

“Well, then, how does she come to be celebrated?”

“Oh, it’s about something, I don’t know what. I never inquired, but I supposed everybody knew.”

For entertainment I often asked these questions myself, of people who were glibly talking about that celebrity and her doings and sayings. The questioned were surprised to find that they had been taking this fame wholly on trust, and had no idea who Olive Logan was or what she had done—if anything.

On the strength of this oddly created notoriety Olive Logan went on the platform, and for at least two seasons the United States flocked to the lecture halls to look at her. She was merely a name and some rich and costly clothes, and neither of these properties had any lasting quality, though for a while they were able to command a fee of $100 a night. She dropped out of the memories of men a quarter of a century ago.

Ralph Keeler was pleasant company on my lecture-flights out of Boston, and we had plenty of good talks and smokes in our rooms after the committee had escorted us to the inn and made their good-night. There was always a committee, and they wore a silk badge of office; they received us at the station and drove us to the lecture hall; they sat in a row of chairs behind me on the stage, minstrel-fashion, and in the earliest days their chief used to introduce me to the audience; but these introductions were so grossly flattering that they made me ashamed, and so I began my talk at a heavy disadvantage. It was a stupid custom; there was no occasion for the introduction; the introducer was almost always an ass, and his prepared speech a jumble of vulgar compliments and dreary efforts to be funny; therefore after the first season I always introduced myself—using, of course, a burlesque of the time-worn introduction. This change was not popular with committee-chairmen. To stand up grandly before a great audience of his townsmen and make his little devilish speech was the joy of his life, and to have that joy taken from him was almost more than he could bear.

My introduction of myself was a most efficient “starter” for a while, then it failed. It had to be carefully and painstakingly worded, and very earnestly spoken, in order that all strangers present might be deceived into the supposition that I was only the introducer and not the lecturer; also that the flow of overdone compliments might sicken those strangers; then, when the end was reached and the remark casually dropped that I was the lecturer and had been talking about myself, the effect was very satisfactory. But it was a good card for only a little while, as I have said; for the newspapers printed it, and after that I could not make it go, since the house knew what was coming and retained its emotions.

Next I tried an introduction taken from my Californian experiences. It was gravely made by a slouching and awkward big miner in the village of Red Dog. The house, very much against his will, forced him to ascend the platform and introduce me. He stood thinking a moment, then said:

“I don’t know anything about this man. At least I know only two things; one is, he hasn’t been in the penitentiary, and the other is (after a pause, and almost sadly), I don’t know why.”

That worked well for a while, then the newspapers printed it and took the juice out of it, and after that I gave up introductions altogether.

Now and then Keeler and I had a mild little adventure, but none which couldn’t be forgotten without much of a strain. Once we arrived late at a town and found no committee in waiting, and no sleighs on the stand. We struck up a street, in the gay moonlight, found a tide of people flowing along, judged it was on its way to the lecture hall—a correct guess—and joined it. At the hall I tried to press in but was stopped by the ticket-taker—

“Ticket, please.”

I bent over and whispered—

“It’s all right—I am the lecturer.”

He closed one eye impressively and said, loud enough for all the crowd to hear—

“No you don’t. Three of you have got in, up to now, but the next lecturer that goes in here to-night pays.”

Of course we paid; it was the least embarrassing way out of the trouble. The very next morning Keeler had an adventure. About eleven o’clock I was sitting in my room reading the paper when he burst into the place all a-tremble with excitement and said—

“Come with me—quick!”

“What is it? what’s happened?”

“Don’t wait to talk—come with me.”

We tramped briskly up the main street three or four blocks, neither of us speaking, both of us excited, I in a sort of panic of apprehension and horrid curiosity, then we plunged into a building and down through the middle of it to the further end. Keeler stopped, put out his hand, and said—

“Look.”

I looked, but saw nothing except a row of books.

“What is it, Keeler?”

He said, in a kind of joyous ecstasy—

“Keep on looking—to the right; further—further to the right. There—see it? ‘Gloverson and His Silent Partners!’”

And there it was, sure enough.

“This is a library! Understand? Public library. And they’ve got it!”

His eyes, his face, his attitude, his gestures, his whole being spoke his delight, his pride, his happiness. It never occurred to me to laugh; a supreme joy like that moves one the other way; I was stirred almost to the crying point to see so perfect a happiness.

He knew all about the book, for he had been cross-examining the librarian. It had been in the library two years, and the records showed that it had been taken out three times.

“And read, too!” said Keeler. “See—the leaves are all cut.”

Moreover, the book had been “bought, not given—it’s on the record.” I think “Gloverson” was published in San Francisco. Other copies had been sold, no doubt, but this present sale was the only one Keeler was certain of. It seems unbelievable that the sale of an edition of one book could give an author this immeasurable peace and contentment, but I was there and I saw it.

Afterward Keeler went out to Ohio and hunted out one of Ossawatomie Brown’s brothers on his farm and took down in long-hand his narrative of his adventures in escaping from Virginia after the tragedy of 1859—the most admirable piece of reporting, I make no doubt, that was ever done by a man destitute of a knowledge of short-hand writing. It was published in the Atlantic Monthly, and I made three attempts to read it but was frightened off each time before I could finish. The tale was so vivid and so real that I seemed to be living those adventures myself and sharing their intolerable perils, and the torture of it all was so sharp that I was never able to follow the story to the end.

By and by the Tribune commissioned Keeler to go to Cuba and report the facts of an outrage or an insult of some sort which the Spanish authorities had been perpetrating upon us according to their well-worn habit and custom. He sailed from New York in the steamer and was last seen alive the night before the vessel reached Havana. It was said that he had not made a secret of his mission, but had talked about it freely, in his frank and innocent way. There were some Spanish military men on board. It may be that he was not flung into the sea; still, the belief was general that that was what had happened.

Clemens wrote the manuscript of “Scraps from My Autobiography. From Chapter IX” (now in the Mark Twain Papers) in London in 1900. He later asked his daughter Jean to type it, probably in 1902, and then lightly revised her typescript. By early August 1906, when George Harvey was induced to read the autobiography in typescript and instantly suggested selections for publication in the North American Review, Cle

mens had already decided not to include this long reminiscence of childhood in his plan for the autobiography. Harvey read Jean’s typescript and chose the first part for the Review, and Josephine Hobby retyped it to make printer’s copy for the 21 September 1906 issue, which Clemens then revised once more (NAR 2). Clemens later decided to publish the second part in the Review as well, making further changes to the text before it appeared in the 3 May 1907 issue (NAR 17). Despite these several layers of revision and the inclusion of almost all of the manuscript in the serial publication, the text was never incorporated into the final form of the autobiography.

Paine misdated the manuscript 1898 and published it as “Playing ‘Bear’—Herrings—Jim Wolf and the Cats,” censoring it in his usual manner (MTA, 1:125–43). For instance, Clemens’s reference to his companion as the “little black slave boy” became just “little black boy,” and his exuberant “Dey eats ’em guts and all!”(twice) became “Dey eats ’em innards and all!”—both softenings that Clemens himself did not make for the Review. Although Neider had access to the original manuscript, he instead copied Paine’s text, inserting a section from the Autobiographical Dictation of 13 February 1906 (AMT, 37–43, 44–47).

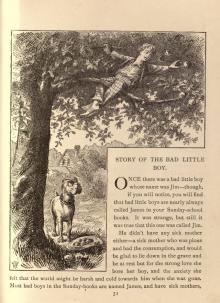

Scraps from My Autobiography

From Chapter IX

This was in 1849.1 was fourteen years old, then. We were still living in Hannibal, Missouri, 1849 on the banks of the Mississippi, in the new “frame” house built by my father five years before. That is, some of us lived in the new part, the rest in the old part back of it—the “L.” In the autumn my sister gave a party, and invited all the marriageable young people of the village. I was too young for this society, and was too bashful to mingle with young ladies anyway, therefore I was not invited—at least not for the whole evening. Ten minutes of it was to be my whole share. I was to do the part of a bear in a small fairy-play. I was to be disguised all over in a close-fitting brown hairy stuff proper for a bear. About half past ten I was told to go to my room and put on this disguise, and be ready in half an hour. I started, but changed my mind; for I wanted to practice a little, and that room was very small. I crossed over to the large unoccupied house on the corner of Main and Hill streets,* unaware that a dozen of the young people were also going there to dress for their parts. I took the little black slave boy, Sandy, with me, and we selected a roomy and empty chamber on the second floor. We entered it talking, and this gave a couple of half-dressed young ladies an opportunity to take refuge behind a screen undiscovered. Their gowns and things were hanging on hooks behind the door, but I did not see them; it was Sandy that shut the door, but all his heart was in the theatricals, and he was as unlikely to notice them as I was myself.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 1.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 1. The Prince and the Pauper

The Prince and the Pauper The American Claimant

The American Claimant Eve's Diary, Complete

Eve's Diary, Complete Extracts from Adam's Diary, translated from the original ms.

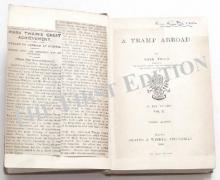

Extracts from Adam's Diary, translated from the original ms. A Tramp Abroad

A Tramp Abroad The Best Short Works of Mark Twain

The Best Short Works of Mark Twain Humorous Hits and How to Hold an Audience

Humorous Hits and How to Hold an Audience The Speculative Fiction of Mark Twain

The Speculative Fiction of Mark Twain The Facts Concerning the Recent Carnival of Crime in Connecticut

The Facts Concerning the Recent Carnival of Crime in Connecticut Alonzo Fitz, and Other Stories

Alonzo Fitz, and Other Stories The $30,000 Bequest, and Other Stories

The $30,000 Bequest, and Other Stories Pudd'nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins

Pudd'nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the Undead

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the Undead Sketches New and Old

Sketches New and Old The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg

The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg A Tramp Abroad — Volume 06

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 06 A Tramp Abroad — Volume 02

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 02 The Prince and the Pauper, Part 1.

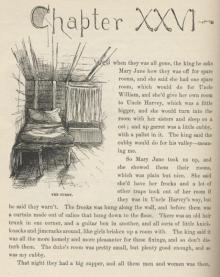

The Prince and the Pauper, Part 1. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 16 to 20

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 16 to 20 The Prince and the Pauper, Part 9.

The Prince and the Pauper, Part 9. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 21 to 25

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 21 to 25 Tom Sawyer, Detective

Tom Sawyer, Detective A Tramp Abroad (Penguin ed.)

A Tramp Abroad (Penguin ed.) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 36 to the Last

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 36 to the Last The Mysterious Stranger, and Other Stories

The Mysterious Stranger, and Other Stories A Tramp Abroad — Volume 03

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 03 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 3.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 3. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 06 to 10

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 06 to 10_preview.jpg) The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade)

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 31 to 35

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 31 to 35 The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg, and Other Stories

The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg, and Other Stories A Tramp Abroad — Volume 07

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 07 Editorial Wild Oats

Editorial Wild Oats Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 26 to 30

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 26 to 30 1601: Conversation as it was by the Social Fireside in the Time of the Tudors

1601: Conversation as it was by the Social Fireside in the Time of the Tudors A Tramp Abroad — Volume 05

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 05 Sketches New and Old, Part 1.

Sketches New and Old, Part 1. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 2.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 2. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 8.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 8. A Tramp Abroad — Volume 01

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 01 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 5.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 5. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 01 to 05

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 01 to 05 A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 1.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 1. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 4.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 4. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 2.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 2. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 7.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 7. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 3.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 3. Sketches New and Old, Part 4.

Sketches New and Old, Part 4. Sketches New and Old, Part 3.

Sketches New and Old, Part 3. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 7.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 7. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 5.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 5. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 6.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 6. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 4.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 4. Sketches New and Old, Part 2.

Sketches New and Old, Part 2. Sketches New and Old, Part 6.

Sketches New and Old, Part 6. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 11 to 15

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 11 to 15 Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc

Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc Sketches New and Old, Part 5.

Sketches New and Old, Part 5. Eve's Diary, Part 3

Eve's Diary, Part 3 Sketches New and Old, Part 7.

Sketches New and Old, Part 7. Mark Twain on Religion: What Is Man, the War Prayer, Thou Shalt Not Kill, the Fly, Letters From the Earth

Mark Twain on Religion: What Is Man, the War Prayer, Thou Shalt Not Kill, the Fly, Letters From the Earth Tales, Speeches, Essays, and Sketches

Tales, Speeches, Essays, and Sketches A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 9.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 9. Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands (version 1)

Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands (version 1) 1601

1601 Letters from the Earth

Letters from the Earth Curious Republic Of Gondour, And Other Curious Whimsical Sketches

Curious Republic Of Gondour, And Other Curious Whimsical Sketches The Mysterious Stranger

The Mysterious Stranger Life on the Mississippi

Life on the Mississippi Roughing It

Roughing It Alonzo Fitz and Other Stories

Alonzo Fitz and Other Stories The 30,000 Dollar Bequest and Other Stories

The 30,000 Dollar Bequest and Other Stories The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn taots-2

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn taots-2 A Double-Barreled Detective Story

A Double-Barreled Detective Story adam's diary.txt

adam's diary.txt A Horse's Tale

A Horse's Tale Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1

Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1 The Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins

The Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins Following the Equator

Following the Equator Goldsmith's Friend Abroad Again

Goldsmith's Friend Abroad Again No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger

No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger The Stolen White Elephant

The Stolen White Elephant The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories

The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories The Curious Republic of Gondour, and Other Whimsical Sketches

The Curious Republic of Gondour, and Other Whimsical Sketches Prince and the Pauper (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Prince and the Pauper (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Portable Mark Twain

The Portable Mark Twain Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Adventures of Tom Sawyer taots-1

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer taots-1 A Double Barrelled Detective Story

A Double Barrelled Detective Story Eve's Diary

Eve's Diary A Dog's Tale

A Dog's Tale The Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts (Literature)

The Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts (Literature) The Complete Short Stories of Mark Twain

The Complete Short Stories of Mark Twain What Is Man? and Other Essays

What Is Man? and Other Essays The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Zombie Jim

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Zombie Jim Who Is Mark Twain?

Who Is Mark Twain? Christian Science

Christian Science The Innocents Abroad

The Innocents Abroad Some Rambling Notes of an Idle Excursion

Some Rambling Notes of an Idle Excursion Autobiography of Mark Twain

Autobiography of Mark Twain Those Extraordinary Twins

Those Extraordinary Twins Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1

Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1