- Home

- Mark Twain

Curious Republic Of Gondour, And Other Curious Whimsical Sketches Page 4

Curious Republic Of Gondour, And Other Curious Whimsical Sketches Read online

Page 4

a little, but I saw that I had brought the whole train together once more

by my delay, and that they were all anxious to drink too-and would have

been long ago if the Arab had not pretended that he was out of water.

So I hastened to pass the vessel to Davis. He took a mouthful, and never

said a word, but climbed off his horse and lay down calmly in the road.

I felt sorry for Davis. It was too late now, though, and Dan was

drinking. Dan got down too, and hunted for a soft place. I thought I

heard Dan say, "That Arab's friends ought to keep him in alcohol or else

take him out and bury him somewhere." All the boys took a drink and

climbed down. It is not well to go into further particulars. Let us

draw the curtain upon this act.

..............................

Well, now, to think that after three changing years I should hear from

that curious old relic again, and see Dan advertising it for sale for the

benefit of a benevolent object. Dan is not treating that present right.

I gave that pipe to him for a keepsake. However, he probably finds that

it keeps away custom and interferes with business. It is the most

convincing inanimate object in all this part of the world, perhaps. Dan

and I were roommates in all that long "Quaker City" voyage, and whenever

I desired to have a little season of privacy I used to fire up on that

pipe and persuade Dan to go out; and he seldom waited to change his

clothes, either. In about a quarter, or from that to three-quarters of a

minute, be would be propping up the smoke-stack on the upper deck and

cursing. I wonder how the faithful old relic is going to sell?

A REMINISCENCE OF THE BACK SETTLEMENTS

Now that corpse [said the undertaker, patting the folded hands of the

deceased approvingly was a brick-every way you took him he was a brick.

He was so real accommodating, and so modest-like and simple in his last

moments. Friends wanted metallic burial case--nothing else would do.

I couldn't get it. There warn't going to be time anybody could see that.

Corpse said never mind, shake him up some kind of a box he could stretch

out in comfortable, he warn't particular 'bout the general style of it.

Said he went more on room than style, any way, in the last final

container. Friends wanted a silver door-plate on the coffin, signifying

who he was and wher, he was from. Now you know a fellow couldn't roust

out such a gaily thing as that in a little country town like this. What

did corpse say? Corpse said, whitewash his old canoe and dob his address

and general destination onto it with a blacking brush and a stencil

plate, long with a verse from some likely hymn or other, and pint him for

the tomb, and mark him C. O. D., and just let him skip along. He warn't

distressed any more than you be--on the contrary just as carm and

collected as a hearse-horse; said he judged that wher' he was going to,

a body would find it considerable better to attract attention by a

picturesque moral character than a natty burial case with a swell

doorplate on it. Splendid man, he was. I'd druther do for a corpse like

that 'n any I've tackled in seven year. There's some satisfaction in

buryin' a man like that. You feel that what you're doing is appreciated.

Lord bless you, so's he got planted before he sp'iled, he was perfectly

satisfied; said his relations meant well, perfectly well, but all them

preparations was bound to delay the thing more or less, and he didn't

wish to be kept layin' round. You never see such a clear head as what he

had--and so carm and so cool. Just a hunk of brains that is what he was.

Perfectly awful. It was a ripping distance from one end of that man's

head to t'other. Often and over again he's had brain fever a-raging in

one place, and the rest of the pile didn't know anything about it--didn't

affect it any more than an Injun insurrection in Arizona affects the

Atlantic States. Well, the relations they wanted a big funeral, but

corpse said he was down on flummery--didn't want any procession--fill the

hearse full of mourners, and get out a stern line and tow him behind.

He was the most down on style of any remains I ever struck. A beautiful,

simple-minded creature--it was what he was, you can depend on that. He

was just set on having things the way he wanted them, and he took a solid

comfort in laying his little plans. He had me measure him and take a

whole raft of directions; then he had a minister stand up behind a long

box with a tablecloth over it and read his funeral sermon, saying

'Angcore, angcore!' at the good places, and making him scratch out every

bit of brag about him, and all the hifalutin; and then he made them trot

out the choir so's he could help them pick out the tunes for the

occasion, and he got them to sing 'Pop Goes the Weasel,' because he'd

always liked that tune when he was downhearted, and solemn music made him

sad; and when they sung that with tears in their eyes (because they all

loved him), and his relations grieving around, he just laid there as

happy as a bug, and trying to beat time and showing all over how much he

enjoyed it; and presently he got worked up and excited; and tried to join

in, for mind you he was pretty proud of his abilities in the singing

line; but the first time he opened his mouth and was just going to spread

himself, his breath took a walk. I never see a man snuffed out so

sudden. Ah, it was a great loss--it was a powerful loss to this poor

little one-horse town. Well, well, well, I hain't got time to be

palavering along here--got to nail on the lid and mosey along with' him;

and if you'll just give me a lift we'll skeet him into the hearse and

meander along. Relations bound to have it so--don't pay no attention to

dying injunctions, minute a corpse's gone; but if I had my way, if I

didn't respect his last wishes and tow him behind the hearse, I'll be

cuss'd. I consider that whatever a corpse wants done for his comfort is

a little enough matter, and a man hain't got no right to deceive him or

take advantage of him--and whatever a corpse trusts me to do I'm a-going

to do, you know, even if it's to stuff him and paint him yaller and keep

him for a keepsake--you hear me!"

He cracked his whip and went lumbering away with his ancient ruin of a

hearse, and I continued my walk with a valuable lesson learned--that a

healthy and wholesome cheerfulness is not necessarily impossible to any

occupation. The lesson is likely to be lasting, for it will take many

months to obliterate the memory of the remarks and circumstances that

impressed it.

A ROYAL COMPLIMENT

The latest report about the Spanish crown is, that it will now be

offered to Prince Alfonso, the second son of the King of Portugal,

who is but five years of age. The Spaniards have hunted through all

the nations of Europe for a King. They tried to get a Portuguese in

the person of Dom-Luis, who is an old ex-monarch; they tried to get

an Italian, in the person of Victor Emanuel's young son, the Duke of

Genoa; they tried to get a Spaniard, in the person of Espartero, who

is an octogenarian. Some of them

desired a French Bourbon,

Montpensier; some of them a Spanish Bourbon, the Prince of Asturias;

some of them an English prince, one of the sons of Queen Victoria.

They have just tried to get the German Prince Leopold; but they have

thought it better to give him up than take a war along with him.

It is a long time since we first suggested to them to try an

American ruler. We can offer them a large number of able and

experienced sovereigns to pick from-men skilled in statesmanship,

versed in the science of government, and adepts in all the arts of

administration--men who could wear the crown with dignity and rule

the kingdom at a reasonable expense.

There is not the least danger of Napoleon threatening them if they

take an American sovereign; in fact, we have no doubt he would be

pleased to support such a candidature. We are unwilling to mention

names--though we have a man in our eye whom we wish they had in

theirs.--New York Tribune.

It would be but an ostentation of modesty to permit such a pointed

reference to myself to pass unnoticed. This is the second time that 'The

Tribune' (no doubt sincerely looking to the best interests of Spain and

the world at large) has done me the great and unusual honour to propose

me as a fit person to fill the Spanish throne. Why 'The Tribune' should

single me out in this way from the midst of a dozen Americans of higher

political prominence, is a problem which I cannot solve. Beyond a

somewhat intimate knowledge of Spanish history and a profound veneration

for its great names and illustrious deeds, I feel that I possess no merit

that should peculiarly recommend me to this royal distinction. I cannot

deny that Spanish history has always been mother's milk to me. I am

proud of every Spanish achievement, from Hernando Cortes's victory at

Thermopylae down to Vasco Nunez de Balboa's discovery of the Atlantic

ocean; and of every splendid Spanish name, from Don Quixote and the Duke

of Wellington down to Don Caesar de Bazan. However, these little graces

of erudition are of small consequence, being more showy than serviceable.

In case the Spanish sceptre is pressed upon me--and the indications

unquestionably are that it will be--I shall feel it necessary to have

certain things set down and distinctly understood beforehand. For

instance: My salary must be paid quarterly in advance. In these

unsettled times it will not do to trust. If Isabella had adopted this

plan, she would be roosting on her ancestral throne to-day, for the

simple reason that her subjects never could have raised three months of a

royal salary in advance, and of course they could not have discharged her

until they had squared up with her. My salary must be paid in gold; when

greenbacks are fresh in a country, they are too fluctuating. My salary

has got to be put at the ruling market rate; I am not going to cut under

on the trade, and they are not going to trail me a long way from home and

then practise on my ignorance and play me for a royal North Adams

Chinaman, by any means. As I understand it, imported kings generally get

five millions a year and house-rent free. Young George of Greece gets

that. As the revenues only yield two millions, he has to take the

national note for considerable; but even with things in that sort of

shape he is better fixed than he was in Denmark, where he had to

eternally stand up because he had no throne to sit on, and had to give

bail for his board, because a royal apprentice gets no salary there while

he is learning his trade. England is the place for that. Fifty thousand

dollars a year Great Britain pays on each royal child that is born, and

this is increased from year to year as the child becomes more and more

indispensable to his country. Look at Prince Arthur. At first he only

got the usual birth-bounty; but now that he has got so that he can dance,

there is simply no telling what wages he gets.

I should have to stipulate that the Spanish people wash more and

endeavour to get along with less quarantine. Do you know, Spain keeps

her ports fast locked against foreign traffic three-fourths of each year,

because one day she is scared about the cholera, and the next about the

plague, and next the measles, next the hooping cough, the hives, and the

rash? but she does not mind leonine leprosy and elephantiasis any more

than a great and enlightened civilisation minds freckles. Soap would

soon remove her anxious distress about foreign distempers. The reason

arable land is so scarce in Spain is because the people squander so much

of it on their persons, and then when they die it is improvidently buried

with them.

I should feel obliged to stipulate that Marshal Serrano be reduced to the

rank of constable, or even roundsman. He is no longer fit to be City

Marshal. A man who refused to be king because he was too old and feeble,

is ill qualified to help sick people to the station-house when they are

armed and their form of delirium tremens is of the exuberant and

demonstrative kind.

I should also require that a force be sent to chase the late Queen

Isabella out of France. Her presence there can work no advantage to

Spain, and she ought to be made to move at once; though, poor thing, she

has been chaste enough heretofore--for a Spanish woman.

I should also require that--

I am at this moment authoritatively informed that "The Tribune" did not

mean me, after all. Very well, I do not care two cents.

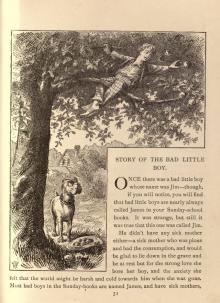

THE APPROACHING EPIDEMIC

One calamity to which the death of Mr. Dickens dooms this country has not

awakened the concern to which its gravity entitles it. We refer to the

fact that the nation is to be lectured to death and read to death all

next winter, by Tom, Dick, and Harry, with poor lamented Dickens for a

pretext. All the vagabonds who can spell will afflict the people with

"readings" from Pickwick and Copperfield, and all the insignificants who

have been ennobled by the notice of the great novelist or transfigured by

his smile will make a marketable commodity of it now, and turn the sacred

reminiscence to the practical use of procuring bread and butter. The

lecture rostrums will fairly swarm with these fortunates. Already the

signs of it are perceptible. Behold how the unclean creatures are

wending toward the dead lion and gathering to the feast:

"Reminiscences of Dickens." A lecture. By John Smith, who heard him

read eight times.

"Remembrances of Charles Dickens." A lecture. By John Jones, who saw

him once in a street car and twice in a barber shop.

"Recollections of Mr. Dickens." A lecture. By John Brown, who gained a

wide fame by writing deliriously appreciative critiques and rhapsodies

upon the great author's public readings; and who shook hands with the

great author upon various occasions, and held converse with him several

times.

"Readings from Dickens." By John White, who has the great delineator's

style and manner perfectly, having attended all his readings in this

country and made these things a study, always practising each reading

<

br /> before retiring, and while it was hot from the great delineator's lips.

Upon this occasion Mr. W. will exhibit the remains of a cigar which he

saw Mr. Dickens smoke. This Relic is kept in a solid silver box made

purposely for it.

"Sights and Sounds of the Great Novelist." A popular lecture. By John

Gray, who ,waited on his table all the time he was at the Grand Hotel,

New York, and still has in his possession and will exhibit to the

audience a fragment of the Last Piece of Bread which the lamented author

tasted in this country.

"Heart Treasures of Precious Moments with Literature's Departed Monarch."

A lecture. By Miss Serena Amelia Tryphenia McSpadden, who still wears,

and will always wear, a glove upon the hand made sacred by the clasp of

Dickens. Only Death shall remove it.

"Readings from Dickens." By Mrs. J. O'Hooligan Murphy, who washed for

him.

"Familiar Talks with the Great Author." A narrative lecture. By John

Thomas, for two weeks his valet in America.

And so forth, and so on. This isn't half the list. The man who has a

"Toothpick once used by Charles Dickens" will have to have a hearing; and

the man who "once rode in an omnibus with Charles Dickens;" and the lady

to whom Charles Dickens "granted the hospitalities of his umbrella during

a storm;" and the person who "possesses a hole which once belonged in a

handkerchief owned by Charles Dickens." Be patient and long-suffering,

good people, for even this does not fill up the measure of what you must

endure next winter. There is no creature in all this land who has had

any personal relations with the late Mr. Dickens, however slight or

trivial, but will shoulder his way to the rostrum and inflict his

testimony upon his helpless countrymen. To some people it is fatal to be

noticed by greatness.

THE TONE-IMPARTING COMMITTEE

I get old and ponderously respectable, only one thing will be able to

make me truly happy, and that will be to be put on the Venerable Tone-

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court

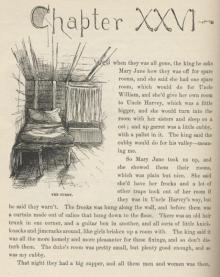

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 1.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 1. The Prince and the Pauper

The Prince and the Pauper The American Claimant

The American Claimant Eve's Diary, Complete

Eve's Diary, Complete Extracts from Adam's Diary, translated from the original ms.

Extracts from Adam's Diary, translated from the original ms. A Tramp Abroad

A Tramp Abroad The Best Short Works of Mark Twain

The Best Short Works of Mark Twain Humorous Hits and How to Hold an Audience

Humorous Hits and How to Hold an Audience The Speculative Fiction of Mark Twain

The Speculative Fiction of Mark Twain The Facts Concerning the Recent Carnival of Crime in Connecticut

The Facts Concerning the Recent Carnival of Crime in Connecticut Alonzo Fitz, and Other Stories

Alonzo Fitz, and Other Stories The $30,000 Bequest, and Other Stories

The $30,000 Bequest, and Other Stories Pudd'nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins

Pudd'nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the Undead

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the Undead Sketches New and Old

Sketches New and Old The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg

The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg A Tramp Abroad — Volume 06

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 06 A Tramp Abroad — Volume 02

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 02 The Prince and the Pauper, Part 1.

The Prince and the Pauper, Part 1. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 16 to 20

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 16 to 20 The Prince and the Pauper, Part 9.

The Prince and the Pauper, Part 9. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 21 to 25

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 21 to 25 Tom Sawyer, Detective

Tom Sawyer, Detective A Tramp Abroad (Penguin ed.)

A Tramp Abroad (Penguin ed.) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 36 to the Last

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 36 to the Last The Mysterious Stranger, and Other Stories

The Mysterious Stranger, and Other Stories A Tramp Abroad — Volume 03

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 03 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 3.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 3. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 06 to 10

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 06 to 10_preview.jpg) The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade)

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 31 to 35

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 31 to 35 The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg, and Other Stories

The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg, and Other Stories A Tramp Abroad — Volume 07

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 07 Editorial Wild Oats

Editorial Wild Oats Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 26 to 30

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 26 to 30 1601: Conversation as it was by the Social Fireside in the Time of the Tudors

1601: Conversation as it was by the Social Fireside in the Time of the Tudors A Tramp Abroad — Volume 05

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 05 Sketches New and Old, Part 1.

Sketches New and Old, Part 1. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 2.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 2. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 8.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 8. A Tramp Abroad — Volume 01

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 01 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 5.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 5. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 01 to 05

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 01 to 05 A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 1.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 1. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 4.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 4. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 2.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 2. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 7.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 7. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 3.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 3. Sketches New and Old, Part 4.

Sketches New and Old, Part 4. Sketches New and Old, Part 3.

Sketches New and Old, Part 3. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 7.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 7. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 5.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 5. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 6.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 6. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 4.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 4. Sketches New and Old, Part 2.

Sketches New and Old, Part 2. Sketches New and Old, Part 6.

Sketches New and Old, Part 6. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 11 to 15

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 11 to 15 Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc

Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc Sketches New and Old, Part 5.

Sketches New and Old, Part 5. Eve's Diary, Part 3

Eve's Diary, Part 3 Sketches New and Old, Part 7.

Sketches New and Old, Part 7. Mark Twain on Religion: What Is Man, the War Prayer, Thou Shalt Not Kill, the Fly, Letters From the Earth

Mark Twain on Religion: What Is Man, the War Prayer, Thou Shalt Not Kill, the Fly, Letters From the Earth Tales, Speeches, Essays, and Sketches

Tales, Speeches, Essays, and Sketches A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 9.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 9. Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands (version 1)

Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands (version 1) 1601

1601 Letters from the Earth

Letters from the Earth Curious Republic Of Gondour, And Other Curious Whimsical Sketches

Curious Republic Of Gondour, And Other Curious Whimsical Sketches The Mysterious Stranger

The Mysterious Stranger Life on the Mississippi

Life on the Mississippi Roughing It

Roughing It Alonzo Fitz and Other Stories

Alonzo Fitz and Other Stories The 30,000 Dollar Bequest and Other Stories

The 30,000 Dollar Bequest and Other Stories The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn taots-2

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn taots-2 A Double-Barreled Detective Story

A Double-Barreled Detective Story adam's diary.txt

adam's diary.txt A Horse's Tale

A Horse's Tale Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1

Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1 The Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins

The Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins Following the Equator

Following the Equator Goldsmith's Friend Abroad Again

Goldsmith's Friend Abroad Again No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger

No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger The Stolen White Elephant

The Stolen White Elephant The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories

The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories The Curious Republic of Gondour, and Other Whimsical Sketches

The Curious Republic of Gondour, and Other Whimsical Sketches Prince and the Pauper (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Prince and the Pauper (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Portable Mark Twain

The Portable Mark Twain Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Adventures of Tom Sawyer taots-1

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer taots-1 A Double Barrelled Detective Story

A Double Barrelled Detective Story Eve's Diary

Eve's Diary A Dog's Tale

A Dog's Tale The Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts (Literature)

The Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts (Literature) The Complete Short Stories of Mark Twain

The Complete Short Stories of Mark Twain What Is Man? and Other Essays

What Is Man? and Other Essays The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Zombie Jim

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Zombie Jim Who Is Mark Twain?

Who Is Mark Twain? Christian Science

Christian Science The Innocents Abroad

The Innocents Abroad Some Rambling Notes of an Idle Excursion

Some Rambling Notes of an Idle Excursion Autobiography of Mark Twain

Autobiography of Mark Twain Those Extraordinary Twins

Those Extraordinary Twins Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1

Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1