- Home

- Mark Twain

Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1 Page 9

Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1 Read online

Page 9

41. L4: 27 June 1871 to OC (2nd of 2), 414; 15 Oct 1871 to OLC, 472 n. 1; 17 Oct 1871 to OLC, 475 n. 1; 24 Oct 1871 to Redpath, 478.

42. “Mark Twain’s Bequest,” datelined “Vienna, May 22,” London Times, 23 May 1899, 4, in Scharnhorst 2006, 332–34; Curtis Brown 1899.

43. 3 Sept 1899 to Murray, CU-MARK.

44. The text was not included in the final form and, like the third manuscript written in 1900, is therefore published in the “Preliminary Manuscripts and Dictations” section of this volume.

45. 31 Dec 1900 to MacAlister, ViU.

46. Harvey for Harper and Brothers to Rogers, 17 Oct 1900, CU-MARK. For Harvey’s biography, see AD, 12 Jan 1906, note at 267.35.

47. Harvey for Harper and Brothers to SLC, 14 Nov 1900, CU-MARK (the term of this 14 November letter agreement was “between this date and January 1st, 1902”); 20 Nov 1900 to Harvey, MH-H; SLC per Harvey to Harvey, 26 Nov 1900, Harper and Row archives, photocopy in CU-MARK.

48. In May 1888, having “spent an hour & a half” with one of Thomas Edison’s recently marketed phonographs “with vast satisfaction,” he tried to leverage his friendship with Edison to secure two of the machines “immediately, instead of having to wait my turn. Then all summer long I could use one of them in Elmira, N. Y., & express the wax cylinders to my helper in Hartford to be put into the phonograph here & the contents transferred to paper by typewriter.” At the end of July, however, when the machines failed to arrive, he canceled the order (25 May 1888 to Edison, NjWoE; SLC per Whitmore to the North American Phonograph Company, 30 July 1888, CU-MARK).

49. SLC 1892; SLC and OLC to Howells, 28 Feb 1891, NN-BGC, in MTHL, 2:637; 4 Apr 1891 to Howells, NN-BGC, in MTHL, 2:641.

50. Lyon 1903–6, entry for 28 Feb 1904. Clemens actually began dictating earlier than 14 January; see “Villa di Quarto”: “I am dictating these informations on this 8th day of January 1904” (233.12–13).

51. 16 Jan 1904 to Howells, MH-H, in MTHL, 2:778–79.

52. Howells to SLC, 14 Feb 1904, CU-MARK, in MTHL, 2:781.

53. 14 Mar 1904 to Howells, NN-BGC, in MTHL, 2:782.

54. “John Hay,” 224.26–39; “The Latest Attempt,” 220.17.

55. Lyon’s longhand notes for these dictations are presumedlost, and one of only two typescripts by Jean Clemens to survive is the first part (twenty-one pages) of the “Villa di Quarto” dictation. With that exception, all the Florentine Dictations are preserved only in typed copies made in 1906 from Jean’s (now lost) typescripts. The dictation about the typewriter was published under the heading “From My Unpublished Autobiography” in Harper’s Weekly for 18 March 1905, and Clemens later inserted it in AD, 27 Feb 1907 (SLC 1905c).

56. See the Textual Commentary for “Villa di Quarto,” MTPO.

57. AD, 6 Aug 1906.

58. 29 Jan 1904 to Stanchfield, CU-MARK.

59. See the ADs of 26 May (Whitford), 2 June (Paige), and 14 June 1906 (Bret Harte).

60. 16 Jan 1904 to Howells, MH-H, in MTHL, 2:779.

61. “Twain’s Plan to Beat the Copyright Law,” New York Times, 12 Dec 1906, 1. The then current copyright law granted protection for twenty-eight years, with one extension of fourteen, for a total term of forty-two years. Clemens thought that if the autobiographical notes were attached to a book at the end of its term, they would create a new publication with its own term of forty-two years, for an overall total of eighty-four years.

62. 21, 22, and 23 Feb 1910 to CC, photocopy in CU-MARK. The “Copyright Act of 1909” passed both houses of Congress on 4 March 1909.

63. MTB, 3:1260–64. The following account of the history of the Autobiographical Dictation series is founded upon and greatly indebted to the ground-breaking research of Lin Salamo, an editor at the Mark Twain Project until 2009.

64 MTB, 3:1266.

65. AD, 9 Jan 1906; Lyon 1906, entry for 25 May; MTB, 3:1266.

66. MTB, 3:1267.

67. If TS1 through TS4 had been preserved in the way they were doubtless left to Paine—as four stacks of consecutively numbered pages—it would long ago have been obvious that each was a discrete sequence. But the pages of each typescript were distributed into individual folders labeled by the date of the relevant dictation, blocking that simple insight.

68. The two later employees were Mary Louise Howden (who began in October 1908) and William Edgar Grumman (who began in February 1909). They worked during a period when work on the autobiography was drawing to a close, and their combined typescripts totaled only slightly more than a hundred pages.

69. Lyon 1906, entry for 13 Mar.

70. Lyon 1906, entries for 8 and 9 Apr; Howells to SLC, 8 Apr 1906, CU-MARK, in MTHL, 2:803–4 (which misidentifies the typescript pages lent to Howells); 8 Apr 1906 to CC, MoPlS and CU-MARK.

71. Lyon 1906, entries for 15 May, 20 May, 25 May, and 21 June; MTB, 3:1307–8.

72. Lyon 1906, entry for 29 Aug. “The King” was the pet name that Lyon and Paine used for Clemens.

73. Lyon 1906, entry for 20 June. Hobby’s stenographic record apparently did not make a distinction between “a” and “one.”

74. Lyon 1906, entry for 27 May; HHR, 697. See “Robert Louis Stevenson and Thomas Bailey Aldrich” for Clemens’s comments on “submerged renown.”

75. 17 June 1906 to Rogers, Salm, in HHR, 611; Rogers to SLC, 4 June 1906, CU-MARK, in HHR, 608.

76. 10 June 1906 to Teller, NN-BGC.

77. Lyon 1906, entries for 8 June and 21 June.

78. Pages 3 and 7 of Lyon’s copy of Paine’s Autobiography, quoted courtesy of Kevin Mac Donnell, its owner. Lyon made her notes in 1947 or 1948.

79. Paine to Lyon, 11 June 1906, CU-MARK; Lyon 1906, entries for 13 and 22 June. Lyon’s date (1879) for this typescript was wrong; she may have intended to write “1897” which would have been about right.

80. 17 June 1906 to Howells, NN-BGC, in MTHL, 2:811; Lyon 1906, entry for 14 June. The sketch Clemens referred to here was “Captain Stormfield’s Visit to Heaven,” a manuscript written as early as 1868 and several times revised. Among the “fat” must have been other unfinished or unpublished manuscripts he later inserted into the autobiography, motivated at least in part by his copyright renewal scheme: “Down the Rhone,” known as “The Innocents Adrift,” written in 1891 (see the Textual Commentary for “Villa di Quarto” at MTPO); and “Wapping Alice,” written in 1898. See the A Ds of 6 June and 9 Apr 1906. Many other such “nonautobiographical” manuscripts were ultimately inserted in the Autobiographical Dictations.

81. Hobby had already begun to retype the forty-four pages, but her typescript (TS2) is also now missing. Collation of the manuscript against another 1906 typescript (TS4) derived from the “old” lost typescript shows that Clemens had revised it (see the next section: “Two More Typescripts: TS2 and TS4”). TS4 has “[1900]” typed at the top, which suggests that the lost typescript included this date.

82. The first draft of the epigraph was inscribed by Clemens in a small calendar notebook for “November, 1901” and identified on the cover as “Autobiography” (CU-MARK). Other notes by Clemens indicate that he was using it in early 1902. The 1906 version, which survives only in a typescript, shows that he revised it on a document that is now missing.

83. For details, see the Appendix “Previous Publication” (pp. 663–67).

84. 17 June 1906 to Howells, NN-BGC, in MTHL, 2:811.

85. The first surviving carbon copy of TS1 is of the 11 June 1906 dictation.

86. The only large difference between TS2 and TS4 is the placement of “John Hay.” In TS4 it precedes “The Latest Attempt” and other prefaces, but it apparently followed them in TS2. The TS2 order is adopted in the present edition on the assumption that TS4 was in error. See the Textual Commentary for “The Latest Attempt” preface, MTPO.

87. Lyon 1906, entry for 21 June.

88. McClure to SLC, 2 July 1906, CU-MARK; 4 June 1906 to Duneka, MFai; 17 June 1906 to Rogers, MFai, in HHR, 611–13; Lyon 1906, entry for 25 July; Harvey to SL

C, 4 June 1906, CU-MARK; McClure to SLC, 2 July 1906, CU-MARK; 3 Aug 1906 to CC, photocopy in CU-MARK.

89. Mott 1938, 219–20, 256–57; Johnson 1935, 73, 205, 268; SLC 1902d, 1903b–d; Lyon 1906, entry for 31 July.

90. 4 and 5 Aug 1906 to Rogers, NNC, in Leary 1961, 39.

91. 3 Aug 1906 to CC, photocopy in CU-MARK. If Howells did help make selections, no sign of it has survived.

92. 7 Aug 1906 to Teller, NN-BGC.

93. See Michael J. Kiskis’s “Afterword” in the facsimile edition of the North American Review installments (SLC 1996), 10–20. Other critical studies of the autobiography include Cox 1966, Krauth 1999, Robinson 2007, and Kiskis’s “Introduction” to SLC 1990.

94. 3 Aug 1906 to CC, photocopy in CU-MARK. Because the TS3 batches contained excerpts from several different Autobiographical Dictations, the way they were filed in the Mark Twain Papers also created a confusing anomaly until their function was understood.

95. Harvey to SLC, 3 or 4 Aug 1906, CU-MARK. Harvey carried away TS3 typescripts of selections intended for installments 1 and 5, and the third batch in progress was for installments 2, 3, and 4.

96. 25–28 Aug 1906 to Rogers, NNC, in Leary 1961, 53. By the time the early installments were published, they had been further rearranged. Harvey’s note to Clemens of 3 or 4 Aug 1906, listing the batches of TS3 he was taking with him (CU-MARK), referred to installments “No. 1” and “No. 5,” which ultimately became installments 3 and 2, respectively; his “Nos. 2, 3 & 4” became 4, 5, and 6.

97. Harvey 1906, 442–43. Clemens used the expression “pier No. 70” in his speech at his seventieth birthday dinner (see the Appendix, pp. 657–61).

98. 25–28 Aug 1906 to Rogers, NNC, in Leary 1961, 45–46.

99. 4 and 5 Aug 1906 to Rogers, NNC, in Leary 1961, 39. Installment 9, published on 4 Jan 1907, was based on ADs from December 1906, which consisted largely of manuscript material.

100. There were twenty-five Review installments in all. See the Appendix “Previous Publication” (pp. 666–67) for a list of all the excerpts and a summary of their contents.

101. See the ADs of 9 Jan, 8 Feb, 28 Mar, 12 Jan, and 9 Feb 1906.

102. For example, on the printer’s copy for NAR 6 Clemens noted, “I think a date necessary now and then. I think they should be let into the margin, David. | M.T.” He had begun adding such marginal dates to guide the reader through his nonchronological narrative when preparing” Scraps from My Autobiography. From Chapter IX” for NAR 2, but Munro had ignored them; they are adopted in this edition. And on the galley proofs of NAR 7 Clemens wrote, “David, if you don’t send stamped & addressed envelops with these things I’ll have your scalp! With love, Mark” (ViU; see the Textual Commentaries for the ADs of 26 Feb and 5 Mar 1906, MTPO). For Munro’s biography see AD, 16 Jan 1906, note at 284.7.

103. New York Times: “Topics of the Week,” 15 Sept 1906, BR568, and 29 Sept 1906, BR602; see AD, 21 May 1906.

104. See the ADs of 1 Feb, 2 Feb, 5 Feb, 8 Feb, and 19 Jan 1906.

105. “Mark Twain’s Memory,” Louisville (Kentucky) Courier-Journal, 20 Nov 1906, 6; see the explanatory notes for the “Random Extracts” sketch.

106. “Mark Twain Declares That His Wife Made Him Swear off Swearing,” Washington Post, 16 Dec 1906, B8; “The Two Sides of It,” Pearson’s Magazine, Jan 1907, 117; this journal was an American affiliate of the British journal of the same name, devoted to literature, politics, and the arts.

107. Lyon 1907, entry for 30 July.

108. Lyon 1907, entry for 9 Sept.

109. See Schmidt 2009b for a detailed comparison of the syndicated texts with those in the North American Review, access to almost all the illustrations, and a record of newspapers known to have carried “Sunday Magazine.”

110. Willing to Unidentified, 28 Oct 1941, photocopy in CU-MARK; Clemens’s words to Willing were a pun on the catch-phrase “Barkis is willing” from David Copperfield (chapter 5).

111. Howells 1910, 93–94.

112. AD, 6 Apr 1906.

113. Clemens was giving a deposition as a plaintiff in a lawsuit involving the land (“Interrogatories for Saml. L. Clemens,” filed 3 April 1909, and “Deposition S. L. Clemens,” filed 11 June 1909, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration 1907–9; copies of these documents provided courtesy of Barbara Schmidt).

114. For Harvey’s 17 Oct 1900 draft of publishing terms for Clemens’s “memoirs in the year 2000,” see p. 19 above. For details of the textual policy and practices applied throughout this edition, see “Note on the Text,” pp. 669–79.

PRELIMINARY MANUSCRIPTS AND DICTATIONS

1870–1905

Clemens wrote this manuscript, now in the Mark Twain Papers, sometime in 1870, leaving it incomplete and without a title (but with space for one on the first page). It is the earliest extant manuscript that might fairly be called a draft chapter for his autobiography, although he did not explicitly identify it as such. He evidently planned to publish it in some way, for he changed the reference to his father’s nemesis from “Ira Stout” to “Ira ——.”

The text has never been accurately published before. Albert Bigelow Paine did include it in Mark Twain’s Autobiography under the title he gave it, “The Tennessee Land,” but he silently omitted the anecdote at the end of the third paragraph (beginning with “A venerable lady . . . “) and changed Clemens’s description of his father as a “candidate for county judge, with a certainty of election” to say instead that he “had been elected to the clerkship of the Surrogate Court” (MTA, 1:3–6; neither description is accurate: see the Appendix “Family Biographies,” p. 654). Charles Neider reprinted the text from the manuscript, restoring the anecdote omitted by Paine but adopting Paine’s changed description of John Marshall Clemens; he also made dozens of his own omissions and changes, and he appended two paragraphs from “My Autobiography [Random Extracts from It],” written in Vienna in 1897–98 (AMT, 22–24). Clemens returned to the subject of the Tennessee land in that manuscript and in the Autobiographical Dictation of 5 April 1906.

John Marshall Clemens’s land purchases and the family’s subsequent sales of the land have been only partly documented from independent sources. The extant grants, deeds, and bills of sale are incomplete, but it was also the case that contradictory or inaccurate deeds often led to disputed claims. Orion Clemens referred to one cause of such conflict in a letter to his brother on 7 July 1869, alleging that “Tennessee grants the same land over and over again to different parties” (OC to SLC, 7 July 1869, CU-MARK, quoted in 3? July 1869 to OC, L3, 279 n. 1 [bottom]; for family correspondence on the subject from 1853 to 1870, see L1, L2, L3, and L4).

[The Tennessee Land]

The monster tract of land which our family own in Tennessee, was purchased by my father a little over forty years ago. He bought the enormous area of seventy-five thousand acres at one purchase. The entire lot must have cost him somewhere in the neighborhood of four hundred dollars. That was a good deal of money to pass over at one payment in those days—at least it was so considered away up there in the pineries and the “Knobs” of the Cumberland Mountains of Fentress county, East Tennessee. When my father paid down that great sum, and turned and stood in the courthouse door of Jamestown, and looked abroad over his vast possessions, he said: “Whatever befalls me, my heirs are secure; I shall not live to see these acres turn to silver and gold, but my children will.” Thus, with the very kindest intentions in the world toward us, he laid the heavy curse of prospective wealth upon our shoulders. He went to his grave in the full belief that he had done us a kindness. It was a woful mistake, but fortunately he never knew it.

He further said: “Iron ore is abundant in this tract, and there are other minerals; there are thousands of acres of the finest yellow pine timber in America, and it can be rafted down Obeds river to the Cumberland, down the Cumberland to the Ohio, down the Ohio to the Mississippi, and down the Mississippi to any community that wants it. There is no end to the tar, pitch and turpentin

e which these vast pineries will yield. This is a natural wine district, too; there are no vines elsewhere in America, cultivated or otherwise, that yield such grapes as grow wild here. There are grazing lands, corn lands, wheat lands, potato lands, there are all species of timber—there is everything in and on this great tract of land that can make land valuable. The United States contain fourteen millions of inhabitants; the population has increased eleven millions in forty years, and will henceforth increase faster than ever; my children will see the day that immigration will push its way to Fentress county, Tennessee, and then, with seventy-five thousand acres of excellent land in their hands, they will become fabulously wealthy.”

Everything my father said about the capabilities of the land was perfectly true—and he could have added with like truth, that there were inexhaustible mines of coal on the land, but the chances are that he knew very little about the article, for the innocent Tennesseeans were not accustomed to digging in the earth for their fuel. And my father might have added to the list of eligibilities, that the land was only a hundred miles from Knoxville, and right where some future line of railway leading south from Cincinnati could not help but pass through it. But he never had seen a railway, and it is barely possible that he had not even heard of such a thing. Curious as it may seem, as late as eight years ago there were people living close to Jamestown who never had heard of a railroad and could not be brought to believe in steamboats. They do not vote for Jackson in Fentress county, they vote for Washington. A venerable lady of that locality said of her son: “Jim’s come back from Kaintuck and fotch a stuck-up gal with him from up thar; and bless you they’ve got more new-fangled notions, massy on us! Common log house ain’t good enough for them—no indeedy!—but they’ve tuck ’n’ gaumed the inside of theirn all over with some kind of nasty disgustin’ truck which they say is all the go in Kaintuck amongst the upper hunky, and which they calls it plarsterin’!”

My eldest brother was four or five years old when the great purchase was made, and my eldest sister was an infant in arms. The rest of us—and we formed the great bulk of the family—came afterwards, and were born along from time to time during the next ten years. Four years after the purchase came the great financial crash of ’34, and in that storm my father’s fortunes were wrecked. From being honored and envied as the most opulent citizen of Fentress county—for outside of his great landed possessions he was considered to be worth not less than three thousand five hundred dollars—he suddenly woke up and found himself reduced to less than one-fourth of that amount. He was a proud man, a silent, austere man, and not a person likely to abide among the scenes of his vanished grandeur and be the target for public commiseration. He gathered together his household and journeyed many tedious days through wilderness solitudes, toward what was then the “Far West,” and at last pitched his tent in the almost invisible little town of Florida, Monroe county, Missouri. He “kept store” there several years, but had no luck, except that I was born to him. He presently removed to Hannibal, and prospered somewhat, and rose to the dignity of justice of the peace, and was candidate for county judge, with a certainty of election, when the summons came which no man may disregard. He had been doing tolerably well, for that age of the world, during the first years of his residence in Hannibal, but ill fortune tripped him once more. He did the friendly office of “going security” for Ira ——, and Ira —— walked off and deliberately took the benefit of the new bankrupt law—a deed which enabled him to live easily and comfortably along till death called for him, but a deed which ruined my father, sent him poor to his grave, and condemned his heirs to a long and discouraging struggle with the world for a livelihood. But my father would brighten up and gather heart, even upon his death-bed, when he thought of the Tennessee land. He said that it would soon make us all rich and happy. And so believing, he died.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 1.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 1. The Prince and the Pauper

The Prince and the Pauper The American Claimant

The American Claimant Eve's Diary, Complete

Eve's Diary, Complete Extracts from Adam's Diary, translated from the original ms.

Extracts from Adam's Diary, translated from the original ms. A Tramp Abroad

A Tramp Abroad The Best Short Works of Mark Twain

The Best Short Works of Mark Twain Humorous Hits and How to Hold an Audience

Humorous Hits and How to Hold an Audience The Speculative Fiction of Mark Twain

The Speculative Fiction of Mark Twain The Facts Concerning the Recent Carnival of Crime in Connecticut

The Facts Concerning the Recent Carnival of Crime in Connecticut Alonzo Fitz, and Other Stories

Alonzo Fitz, and Other Stories The $30,000 Bequest, and Other Stories

The $30,000 Bequest, and Other Stories Pudd'nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins

Pudd'nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the Undead

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the Undead Sketches New and Old

Sketches New and Old The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg

The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg A Tramp Abroad — Volume 06

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 06 A Tramp Abroad — Volume 02

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 02 The Prince and the Pauper, Part 1.

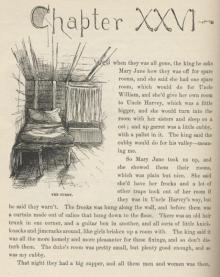

The Prince and the Pauper, Part 1. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 16 to 20

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 16 to 20 The Prince and the Pauper, Part 9.

The Prince and the Pauper, Part 9. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 21 to 25

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 21 to 25 Tom Sawyer, Detective

Tom Sawyer, Detective A Tramp Abroad (Penguin ed.)

A Tramp Abroad (Penguin ed.) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 36 to the Last

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 36 to the Last The Mysterious Stranger, and Other Stories

The Mysterious Stranger, and Other Stories A Tramp Abroad — Volume 03

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 03 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 3.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 3. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 06 to 10

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 06 to 10_preview.jpg) The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade)

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 31 to 35

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 31 to 35 The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg, and Other Stories

The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg, and Other Stories A Tramp Abroad — Volume 07

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 07 Editorial Wild Oats

Editorial Wild Oats Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 26 to 30

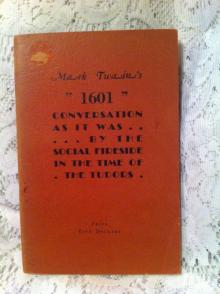

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 26 to 30 1601: Conversation as it was by the Social Fireside in the Time of the Tudors

1601: Conversation as it was by the Social Fireside in the Time of the Tudors A Tramp Abroad — Volume 05

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 05 Sketches New and Old, Part 1.

Sketches New and Old, Part 1. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 2.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 2. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 8.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 8. A Tramp Abroad — Volume 01

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 01 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 5.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 5. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 01 to 05

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 01 to 05 A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 1.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 1. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 4.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 4. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 2.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 2. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 7.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 7. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 3.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 3. Sketches New and Old, Part 4.

Sketches New and Old, Part 4. Sketches New and Old, Part 3.

Sketches New and Old, Part 3. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 7.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 7. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 5.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 5. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 6.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 6. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 4.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 4. Sketches New and Old, Part 2.

Sketches New and Old, Part 2. Sketches New and Old, Part 6.

Sketches New and Old, Part 6. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 11 to 15

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 11 to 15 Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc

Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc Sketches New and Old, Part 5.

Sketches New and Old, Part 5. Eve's Diary, Part 3

Eve's Diary, Part 3 Sketches New and Old, Part 7.

Sketches New and Old, Part 7. Mark Twain on Religion: What Is Man, the War Prayer, Thou Shalt Not Kill, the Fly, Letters From the Earth

Mark Twain on Religion: What Is Man, the War Prayer, Thou Shalt Not Kill, the Fly, Letters From the Earth Tales, Speeches, Essays, and Sketches

Tales, Speeches, Essays, and Sketches A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 9.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 9. Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands (version 1)

Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands (version 1) 1601

1601 Letters from the Earth

Letters from the Earth Curious Republic Of Gondour, And Other Curious Whimsical Sketches

Curious Republic Of Gondour, And Other Curious Whimsical Sketches The Mysterious Stranger

The Mysterious Stranger Life on the Mississippi

Life on the Mississippi Roughing It

Roughing It Alonzo Fitz and Other Stories

Alonzo Fitz and Other Stories The 30,000 Dollar Bequest and Other Stories

The 30,000 Dollar Bequest and Other Stories The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn taots-2

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn taots-2 A Double-Barreled Detective Story

A Double-Barreled Detective Story adam's diary.txt

adam's diary.txt A Horse's Tale

A Horse's Tale Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1

Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1 The Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins

The Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins Following the Equator

Following the Equator Goldsmith's Friend Abroad Again

Goldsmith's Friend Abroad Again No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger

No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger The Stolen White Elephant

The Stolen White Elephant The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories

The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories The Curious Republic of Gondour, and Other Whimsical Sketches

The Curious Republic of Gondour, and Other Whimsical Sketches Prince and the Pauper (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Prince and the Pauper (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Portable Mark Twain

The Portable Mark Twain Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Adventures of Tom Sawyer taots-1

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer taots-1 A Double Barrelled Detective Story

A Double Barrelled Detective Story Eve's Diary

Eve's Diary A Dog's Tale

A Dog's Tale The Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts (Literature)

The Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts (Literature) The Complete Short Stories of Mark Twain

The Complete Short Stories of Mark Twain What Is Man? and Other Essays

What Is Man? and Other Essays The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Zombie Jim

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Zombie Jim Who Is Mark Twain?

Who Is Mark Twain? Christian Science

Christian Science The Innocents Abroad

The Innocents Abroad Some Rambling Notes of an Idle Excursion

Some Rambling Notes of an Idle Excursion Autobiography of Mark Twain

Autobiography of Mark Twain Those Extraordinary Twins

Those Extraordinary Twins Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1

Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1