- Home

- Mark Twain

Christian Science Page 9

Christian Science Read online

Page 9

It is curious and interesting to note with what an unerring instinct the Pastor Emeritus has thought out and forecast all possible encroachments upon her planned autocracy, and barred the way against them, in the By-laws which she framed and copyrighted—under the guidance of the Supreme Being.

THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS

For instance, when Article I. speaks of a President and Board of Directors, you think you have discovered a formidable check upon the powers and ambitions of the honorary pastor, the ornamental pastor, the functionless pastor, the Pastor Emeritus, but it is a mistake. These great officials are of the phrase—family of the Church-Without-a-Creed and the Pastor-With-Nothing-to-Do; that is to say, of the family of Large-Names-Which-Mean-Nothing. The Board is of so little consequence that the By-laws do not state how it is chosen, nor who does it; but they do state, most definitely, that the Board cannot fill a vacancy in its number "except the candidate is approved by the Pastor Emeritus."

The "candidate." The Board cannot even proceed to an election until the Pastor Emeritus has examined the list and squelched such candidates as are not satisfactory to her.

Whether the original first Board began as the personal property of Mrs. Eddy or not, it is foreseeable that in time, under this By-law, she would own it. Such a first Board might chafe under such a rule as that, and try to legislate it out of existence some day. But Mrs. Eddy was awake. She foresaw that danger, and added this ingenious and effective clause:

"This By-law can neither be amended nor annulled, except by consent of Mrs. Eddy, the Pastor Emeritus."

THE PRESIDENT

The Board of Directors, or Serfs, or Ciphers, elects the President.

On these clearly worded terms: "Subject to the approval of the Pastor Emeritus."

Therefore She elects him.

A long term can invest a high official with influence and power, and make him dangerous. Mrs. Eddy reflected upon that; so she limits the President's term to a year. She has a capable commercial head, an organizing head, a head for government.

TREASURER AND CLERK

There are a Treasurer and a Clerk. They are elected by the Board of Directors. That is to say, by Mrs. Eddy.

Their terms of office expire on the first Tuesday in June of each year, "or upon the election of their successors." They must be watchfully obedient and satisfactory to her, or she will elect and install their successors with a suddenness that can be unpleasant to them. It goes without saying that the Treasurer manages the Treasury to suit Mrs. Eddy, and is in fact merely Temporary Deputy Treasurer.

Apparently the Clerk has but two duties to perform: to read messages from Mrs. Eddy to First Members assembled in solemn Council, and provide lists of candidates for Church membership. The select body entitled First Members are the aristocracy of the Mother-Church, the Charter Members, the Aborigines, a sort of stylish but unsalaried little College of Cardinals, good for show, but not indispensable. Nobody is indispensable in Mrs. Eddy's empire; she sees to that.

When the Pastor Emeritus sends a letter or message to that little Sanhedrin, it is the Clerk's "imperative duty" to read it "at the place and time specified." Otherwise, the world might come to an end. These are fine, large frills, and remind us of the ways of emperors and such. Such do not use the penny-post, they send a gilded and painted special messenger, and he strides into the Parliament, and business comes to a sudden and solemn and awful stop; and in the impressive hush that follows, the Chief Clerk reads the document. It is his "imperative duty." If he should neglect it, his official life would end. It is the same with this Mother-Church Clerk; "if he fail to perform this important function of his office," certain majestic and unshirkable solemnities must follow: a special meeting "shall" be called; a member of the Church "shall" make formal complaint; then the Clerk "shall" be "removed from office." Complaint is sufficient, no trial is necessary.

There is something very sweet and juvenile and innocent and pretty about these little tinsel vanities, these grave apings of monarchical fuss and feathers and ceremony, here on our ostentatiously democratic soil. She is the same lady that we found in the Autobiography, who was so naively vain of all that little ancestral military riffraff that she had dug up and annexed. A person's nature never changes. What it is in childhood, it remains. Under pressure, or a change of interest, it can partially or wholly disappear from sight, and for considerable stretches of time, but nothing can ever permanently modify it, nothing can ever remove it.

BOARD OF TRUSTEES

There isn't any—now. But with power and money piling up higher and higher every day and the Church's dominion spreading daily wider and farther, a time could come when the envious and ambitious could start the idea that it would be wise and well to put a watch upon these assets—a watch equipped with properly large authority. By custom, a Board of Trustees. Mrs. Eddy has foreseen that probability—for she is a woman with a long, long look ahead, the longest look ahead that ever a woman had—and she has provided for that emergency. In Art. I., Sec. 5, she has decreed that no Board of Trustees shall ever exist in the Mother-Church "except it be constituted by the Pastor Emeritus."

The magnificence of it, the daring of it! Thus far, she is:

The Massachusetts Metaphysical College; Pastor Emeritus; President; Board of Directors; Treasurer; Clerk; and future Board of Trustees; and is still moving onward, ever onward. When I contemplate her from a commercial point of view, there are no words that can convey my admiration of her.

READERS

These are a feature of first importance in the church-machinery of Christian Science. For they occupy the pulpit. They hold the place that the preacher holds in the other Christian Churches. They hold that place, but they do not preach. Two of them are on duty at a time—a man and a woman. One reads a passage from the Bible, the other reads the explanation of it from Science and Health—and so they go on alternating. This constitutes the service—this, with choir-music. They utter no word of their own. Art. IV., Sec. 6, closes their mouths with this uncompromising gag:

"They shall make no remarks explanatory of the Lesson-Sermon at any time during the service."

It seems a simple little thing. One is not startled by it at a first reading of it; nor at the second, nor the third. One may have to read it a dozen times before the whole magnitude of it rises before the mind. It far and away oversizes and outclasses the best business-idea yet invented for the safe-guarding and perpetuating of a religion. If it had been thought of and put in force eighteen hundred and seventy years ago, there would be but one Christian sect in the world now, instead of ten dozens of them.

There are many varieties of men in the world, consequently there are many varieties of minds in its pulpits. This insures many differing interpretations of important Scripture texts, and this in turn insures the splitting up of a religion into many sects. It is what has happened; it was sure to happen.

Mrs. Eddy has noted this disastrous result of preaching, and has put up the bars. She will have no preaching in her Church. She has explained all essential Scriptures, and set the explanations down in her book. In her belief her underlings cannot improve upon those explanations, and in that stern sentence "they shall make no explanatory remarks" she has barred them for all time from trying. She will be obeyed; there is no question about that.

In arranging her government she has borrowed ideas from various sources—not poor ones, but the best in the governmental market—but this one is new, this one came out of no ordinary business-head, this one must have come out of her own, there has been no other commercial skull in a thousand centuries that was equal to it. She has borrowed freely and wisely, but I am sure that this idea is many times larger than all her borrowings bulked together. One must respect the business-brain that produced it—the splendid pluck and impudence that ventured to promulgate it, anyway.

ELECTION OF READERS

Readers are not taken at hap-hazard, any more than preachers are taken at hap-hazard for the pulpits of other sects. N

o, Readers are elected by the Board of Directors. But—

"Section 3. The Board shall inform the Pas. for Emeritus of the names of candidates for Readers before they are elected, and if she objects to the nomination, said candidates shall not be chosen."

Is that an election—by the Board? Thus far I have not been able to find out what that Board of Spectres is for. It certainly has no real function, no duty which the hired girl could not perform, no office beyond the mere recording of the autocrat's decrees.

There are no dangerously long office-terms in Mrs. Eddy's government. The Readers are elected for but one year. This insures their subserviency to their proprietor.

Readers are not allowed to copy out passages and read them from the manuscript in the pulpit; they must read from Mrs. Eddy's book itself. She is right. Slight changes could be slyly made, repeated, and in time get acceptance with congregations. Branch sects could grow out of these practices. Mrs. Eddy knows the human race, and how far to trust it. Her limit is not over a quarter of an inch. It is all that a wise person will risk.

Mrs. Eddy's inborn disposition to copyright everything, charter everything, secure the rightful and proper credit to herself for everything she does, and everything she thinks she does, and everything she thinks, and everything she thinks she thinks or has thought or intends to think, is illustrated in Sec. 5 of Art. IV., defining the duties of official Readers—in church:

"Naming Book and Author. The Reader of Science and Health, with Key to the Scriptures, before commencing to read from this book, shall distinctly announce its full title and give the author's name."

Otherwise the congregation might get the habit of forgetting who (ostensibly) wrote the book.

THE ARISTOCRACY

This consists of First Members and their apostolic succession. It is a close corporation, and its membership limit is one hundred. Forty will answer, but if the number fall below that, there must be an election, to fill the grand quorum.

This Sanhedrin can't do anything of the slightest importance, but it can talk. It can "discuss." That is, it can discuss "important questions relative to Church members", evidently persons who are already Church members. This affords it amusement, and does no harm.

It can "fix the salaries of the Readers."

Twice a year it "votes on" admitting candidates. That is, for Church membership. But its work is cut out for it beforehand, by Art. IX.:

"Every recommendation for membership In the Church 'shall be countersigned by a loyal student of Mrs. Eddy's, by a Director of this Church, or by a First Member.'"

All these three classes of beings are the personal property of Mrs. Eddy. She has absolute control of the elections.

Also it must "transact any Church business that may properly come before it."

"Properly" is a thoughtful word. No important business can come before it. The By laws have attended to that. No important business goes before any one for the final word except Mrs. Eddy. She has looked to that.

The Sanhedrin "votes on" candidates for admission to its own body. But is its vote worth any more than mine would be? No, it isn't. Sec. 4, of Art. V.—Election of First Members—makes this quite plain:

"Before being elected, the candidates for First Members shall be approved by the Pastor Emeritus over her own signature."

Thus the Sanhedrin is the personal property of Mrs. Eddy. She owns it. It has no functions, no authority, no real existence. It is another Board of Shadows. Mrs. Eddy is the Sanhedrin herself.

But it is time to foot up again and "see where we are at." Thus far, Mrs. Eddy is:

The Massachusetts Metaphysical College; Pastor Emeritus, President; Board of Directors; Treasurer; Clerk; Future Board of Trustees; Proprietor of the Priesthood: Dictator of the Services; Proprietor of the Sanhedrin. She has come far, and is still on her way.

CHURCH MEMBERSHIP

In this Article there is another exhibition of a couple of the large features of Mrs. Eddy's remarkable make-up: her business-talent and her knowledge of human nature.

She does not beseech and implore people to join her Church. She knows the human race better than that. She gravely goes through the motions of reluctantly granting admission to the applicant as a favor to him. The idea is worth untold shekels. She does not stand at the gate of the fold with welcoming arms spread, and receive the lost sheep with glad emotion and set up the fatted calf and invite the neighbor and have a time. No, she looks upon him coldly, she snubs him, she says:

"Who are you? Who is your sponsor? Who asked you to come here? Go away, and don't come again until you are invited."

It is calculated to strikingly impress a person accustomed to Moody and Sankey and Sam Jones revivals; accustomed to brain-turning appeals to the unknown and unendorsed sinner to come forward and enter into the joy, etc.—"just as he is"; accustomed to seeing him do it; accustomed to seeing him pass up the aisle through sobbing seas of welcome, and love, and congratulation, and arrive at the mourner's bench and be received like a long-lost government bond.

No, there is nothing of that kind in Mrs. Eddy's system. She knows that if you wish to confer upon a human being something which he is not sure he wants, the best way is to make it apparently difficult for him to get it—then he is no son of Adam if that apple does not assume an interest in his eyes which it lacked before. In time this interest can grow into desire. Mrs. Eddy knows that when you cannot get a man to try—free of cost—a new and effective remedy for a disease he is afflicted with, you can generally sell it to him if you will put a price upon it which he cannot afford. When, in the beginning, she taught Christian Science gratis (for good reasons), pupils were few and reluctant, and required persuasion; it was when she raised the limit to three hundred dollars for a dollar's worth that she could not find standing room for the invasion of pupils that followed.

With fine astuteness she goes through the motions of making it difficult to get membership in her Church. There is a twofold value in this system: it gives membership a high value in the eyes of the applicant; and at the same time the requirements exacted enable Mrs. Eddy to keep him out if she has doubts about his value to her. A word further as to applications for membership:

"Applications of students of the Metaphysical College must be signed by the Board of Directors."

That is safe. Mrs. Eddy is proprietor of that Board.

Children of twelve may be admitted if invited by "one of Mrs. Eddy's loyal students, or by a First Member, or by a Director."

These sponsors are the property of Mrs. Eddy, therefore her Church is safeguarded from the intrusion of undesirable children.

Other Students. Applicants who have not studied with Mrs. Eddy can get in only "by invitation and recommendation from students of Mrs. Eddy.... or from members of the Mother-Church."

Other paragraphs explain how two or three other varieties of applicants are to be challenged and obstructed, and tell us who is authorized to invite them, recommend them endorse them, and all that.

The safeguards are definite, and would seem to be sufficiently strenuous—to Mr. Sam Jones, at any rate. Not for Mrs. Eddy. She adds this clincher:

"The candidates be elected by a majority vote of the First Members present."

That is the aristocracy, the aborigines, the Sanhedrin. It is Mrs. Eddy's property. She herself is the Sanhedrin. No one can get into the Church if she wishes to keep him out.

This veto power could some time or other have a large value for her, therefore she was wise to reserve it.

It is likely that it is not frequently used. It is also probable that the difficulties attendant upon getting admission to membership have been instituted more to invite than to deter, more to enhance the value of membership and make people long for it than to make it really difficult to get. I think so, because the Mother. Church has many thousands of members more than its building can accommodate.

AND SOME ENGLISH REQUIRED

Mrs. Eddy is very particular as regards one detail curiously so,

for her, all things considered. The Church Readers must be "good English scholars"; they must be "thorough English scholars."

She is thus sensitive about the English of her subordinates for cause, possibly. In her chapter defining the duties of the Clerk there is an indication that she harbors resentful memories of an occasion when the hazy quality of her own English made unforeseen and mortifying trouble:

"Understanding Communications. Sec. 2. If the Clerk of this Church shall receive a communication from the Pastor Emeritus which he does not fully understand, he shall inform her of this fact before presenting it to the Church, and obtain a clear understanding of the matter—then act in accordance therewith."

She should have waited to calm down, then, but instead she added this, which lacks sugar:

"Failing to adhere to this By-law, the Clerk must resign."

I wish I could see that communication that broke the camel's back. It was probably the one beginning: "What plague spot or bacilli were gnawing at the heart of this metropolis and bringing it on bended knee?" and I think it likely that the kindly disposed Clerk tried to translate it into English and lost his mind and had to go to the hospital. That Bylaw was not the offspring of a forecast, an intuition, it was certainly born of a sorrowful experience. Its temper gives the fact away.

The little book of By-laws has manifestly been tinkered by one of Mrs. Eddy's "thorough English scholars," for in the majority of cases its meanings are clear. The book is not even marred by Mrs. Eddy's peculiar specialty—lumbering clumsinesses of speech. I believe the salaried polisher has weeded them all out but one. In one place, after referring to Science and Health, Mrs. Eddy goes on to say "the Bible and the above-named book, with other works by the same author," etc.

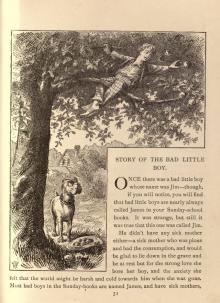

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 1.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 1. The Prince and the Pauper

The Prince and the Pauper The American Claimant

The American Claimant Eve's Diary, Complete

Eve's Diary, Complete Extracts from Adam's Diary, translated from the original ms.

Extracts from Adam's Diary, translated from the original ms. A Tramp Abroad

A Tramp Abroad The Best Short Works of Mark Twain

The Best Short Works of Mark Twain Humorous Hits and How to Hold an Audience

Humorous Hits and How to Hold an Audience The Speculative Fiction of Mark Twain

The Speculative Fiction of Mark Twain The Facts Concerning the Recent Carnival of Crime in Connecticut

The Facts Concerning the Recent Carnival of Crime in Connecticut Alonzo Fitz, and Other Stories

Alonzo Fitz, and Other Stories The $30,000 Bequest, and Other Stories

The $30,000 Bequest, and Other Stories Pudd'nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins

Pudd'nhead Wilson and Those Extraordinary Twins The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the Undead

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and the Undead Sketches New and Old

Sketches New and Old The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg

The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg A Tramp Abroad — Volume 06

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 06 A Tramp Abroad — Volume 02

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 02 The Prince and the Pauper, Part 1.

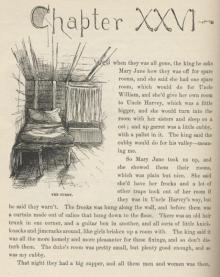

The Prince and the Pauper, Part 1. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 16 to 20

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 16 to 20 The Prince and the Pauper, Part 9.

The Prince and the Pauper, Part 9. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 21 to 25

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 21 to 25 Tom Sawyer, Detective

Tom Sawyer, Detective A Tramp Abroad (Penguin ed.)

A Tramp Abroad (Penguin ed.) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 36 to the Last

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 36 to the Last The Mysterious Stranger, and Other Stories

The Mysterious Stranger, and Other Stories A Tramp Abroad — Volume 03

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 03 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 3.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 3. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 06 to 10

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 06 to 10_preview.jpg) The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade)

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade) Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 31 to 35

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 31 to 35 The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg, and Other Stories

The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg, and Other Stories A Tramp Abroad — Volume 07

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 07 Editorial Wild Oats

Editorial Wild Oats Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 26 to 30

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 26 to 30 1601: Conversation as it was by the Social Fireside in the Time of the Tudors

1601: Conversation as it was by the Social Fireside in the Time of the Tudors A Tramp Abroad — Volume 05

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 05 Sketches New and Old, Part 1.

Sketches New and Old, Part 1. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 2.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 2. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 8.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 8. A Tramp Abroad — Volume 01

A Tramp Abroad — Volume 01 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 5.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 5. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 01 to 05

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 01 to 05 A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 1.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 1. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 4.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 4. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 2.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 2. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 7.

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Part 7. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 3.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 3. Sketches New and Old, Part 4.

Sketches New and Old, Part 4. Sketches New and Old, Part 3.

Sketches New and Old, Part 3. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 7.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 7. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 5.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 5. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 6.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 6. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 4.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 4. Sketches New and Old, Part 2.

Sketches New and Old, Part 2. Sketches New and Old, Part 6.

Sketches New and Old, Part 6. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 11 to 15

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapters 11 to 15 Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc

Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc Sketches New and Old, Part 5.

Sketches New and Old, Part 5. Eve's Diary, Part 3

Eve's Diary, Part 3 Sketches New and Old, Part 7.

Sketches New and Old, Part 7. Mark Twain on Religion: What Is Man, the War Prayer, Thou Shalt Not Kill, the Fly, Letters From the Earth

Mark Twain on Religion: What Is Man, the War Prayer, Thou Shalt Not Kill, the Fly, Letters From the Earth Tales, Speeches, Essays, and Sketches

Tales, Speeches, Essays, and Sketches A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 9.

A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, Part 9. Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands (version 1)

Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands (version 1) 1601

1601 Letters from the Earth

Letters from the Earth Curious Republic Of Gondour, And Other Curious Whimsical Sketches

Curious Republic Of Gondour, And Other Curious Whimsical Sketches The Mysterious Stranger

The Mysterious Stranger Life on the Mississippi

Life on the Mississippi Roughing It

Roughing It Alonzo Fitz and Other Stories

Alonzo Fitz and Other Stories The 30,000 Dollar Bequest and Other Stories

The 30,000 Dollar Bequest and Other Stories The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn taots-2

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn taots-2 A Double-Barreled Detective Story

A Double-Barreled Detective Story adam's diary.txt

adam's diary.txt A Horse's Tale

A Horse's Tale Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1

Autobiography Of Mark Twain, Volume 1 The Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins

The Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins Following the Equator

Following the Equator Goldsmith's Friend Abroad Again

Goldsmith's Friend Abroad Again No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger

No. 44, The Mysterious Stranger The Stolen White Elephant

The Stolen White Elephant The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories

The $30,000 Bequest and Other Stories The Curious Republic of Gondour, and Other Whimsical Sketches

The Curious Republic of Gondour, and Other Whimsical Sketches Prince and the Pauper (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Prince and the Pauper (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Portable Mark Twain

The Portable Mark Twain Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) The Adventures of Tom Sawyer taots-1

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer taots-1 A Double Barrelled Detective Story

A Double Barrelled Detective Story Eve's Diary

Eve's Diary A Dog's Tale

A Dog's Tale The Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts (Literature)

The Mysterious Stranger Manuscripts (Literature) The Complete Short Stories of Mark Twain

The Complete Short Stories of Mark Twain What Is Man? and Other Essays

What Is Man? and Other Essays The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Zombie Jim

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and Zombie Jim Who Is Mark Twain?

Who Is Mark Twain? Christian Science

Christian Science The Innocents Abroad

The Innocents Abroad Some Rambling Notes of an Idle Excursion

Some Rambling Notes of an Idle Excursion Autobiography of Mark Twain

Autobiography of Mark Twain Those Extraordinary Twins

Those Extraordinary Twins Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1

Autobiography of Mark Twain: The Complete and Authoritative Edition, Volume 1